THE PROBLEM WITH THE MARQUIS DE SADE

Sinner

On the eve of the French Revolution in 1789, a prisoner being held in the Bastille shouted down to the street, falsely, that he and the other inmates were being abused and that the people should liberate them. If anyone on the street below had recognized Donatien Alphonse Francois, a.k.a. the Marquis de Sade, it might have seemed ironic that a man notorious for flogging prostitutes would plead for mercy for being mistreated. In addition to having been placed under house arrest and confined to an insane asylum, Sade was repeatedly jailed for his sexual misconduct and libertine dementia. It wasn’t until his incarceration that he began his literary career, at age 50.

*

Sade was born in 1740 to an aristocratic family and spent his late teens in the military. As a young man, Sade discovered that he not only liked rough sex—and pushing sensual experience to the extreme—but also the excitement of knowing he was committing a crime. He engaged in orgies and affairs, often disappearing for long periods while his wife was left alone with the children. And if he was often cruel, he became especially so to prostitutes who confessed to believing in the Church. “The idea of God is the sole wrong for which I cannot forgive mankind,” he wrote in one of his many novels.

At 23, not long after he married a young heiress, Sade procured the services of Mlle. Testard, a comely teenage prostitute who worked the outskirts of Paris. Sade asked Testard if she held religious convictions, and when she said she did, he harangued her with vile and degrading insults and masturbated into a chalice. He also called the Lord a “motherfucker” and inserted two communion hosts into the girl before violating her himself, all the while screaming “If thou art God, avenge thyself.”

He then asked her to heat a cat-o-nine-tails until it glowed red and to beat him with it. When she refused to let him beat her in reciprocation, he masturbated with two crucifixes, held her at knife-point, and forced her to repeat a litany of blasphemies. Scandal erupted immediately, but Sade avoided arrest by hiding out in his country chateau.

Other scandals would follow: one Easter morning Sade noticed Rose Kellor begging alms outside a church. Unemployed and desperate, Kellor agreed to work as a servant in Sade’s household. But when they arrived home, Sade became enraged and ripped off her clothes, throwing her on the bed face down, and assaulted her by whipping her backside until she bled. Her screams of terror only seemed to assist him in reaching climax, which caused Sade to scream in unison with her.

When the half-naked woman arrived at the police station covered in her own blood, it was the beginning of a furor that would ultimately lead to Sade’s arrest. His humiliated wife came to his assistance—as she often did—and bribed Kellor to drop the charges, but the police persisted and the affair resulted in years of legal problems for Sade.

Sade’s addiction to sexual deviance was such it seemed that nothing but jail could stop him. Forced by her husband’s many years in prison (along with her newfound religious zeal), Sade’s wife and protector finally abandoned him.

Shortly after the outbreak of the French Revolution, Sade was released from the Bastille, though not for his desperate lies shouted down to the street. Afterwards, he seemed to lead a quieter life. He involved himself in politics, representing his district of Paris, and for the most part avoided controversy (or assaulting women). He spent much of his twilight focused on what had sustained him in prison: literature. If prison offered no opportunity to titillate his senses with prostitutes, orgies, beatings, and blasphemous sex, then he would channel those fantasies into his novels and plays.

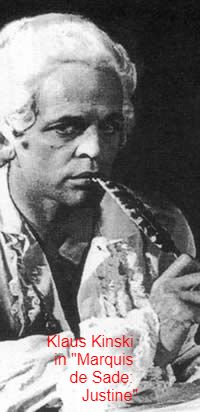

Though his writing style is reminiscent of Horatio Alger’s in its didactic handling of the pantheon of virtues, a Sadian novel or play (as differentiated from “sadistic"—though they were that, too) is anything but a rags-to-riches story. In fact, by observing each of ten traditional virtues Sade cites, the title character of Justine is abused and preyed upon by a conniving and opportunistic society —raped, brutalized, manipulated, robbed, tricked, molested. Sade’s work was graphic for its time, and one critic remarked that if Sade’s novels fell into the hands of soldiers, 20,000 women would be raped.

Sade died in 1814, buried as per his instructions in an unmarked grave that was allowed to grow wild. His influence would be immeasurable. Upon publishing Sade, Apollinaire declared that Sade’s writings would dominate the 20th Century. Henry Miller called Sade the most maligned, misunderstood figure in letters. In 1840, a full century after his birth, the word “sadism” entered the dictionary for the first time. The Encyclopedia Britannica defines sadism as a “psychosexual disorder in which sexual urges are gratified by the infliction of pain on another person.” It would be decades before “sadism” would be paired with “masochism,” although the two seem, at least in Sade’s example, bound inextricably today.

Sade repeatedly wrote that the more aware he was that his behavior was criminal the more it excited him. And ironically, in cases like Sade’s, the punishment that most inflicted psychological anguish as well as physical restrictions—i.e., that most punished Sade—was perhaps the best reward. If the confinement didn’t excite him like a good flogging, at least it helped spur something a little less fleeting than sensual pleasure, his writing life. But his wild life raises a paradox perhaps for the first time: How do you punish a masochist?

Originally published in Killing the Buddha

On the eve of the French Revolution in 1789, a prisoner being held in the Bastille shouted down to the street, falsely, that he and the other inmates were being abused and that the people should liberate them. If anyone on the street below had recognized Donatien Alphonse Francois, a.k.a. the Marquis de Sade, it might have seemed ironic that a man notorious for flogging prostitutes would plead for mercy for being mistreated. In addition to having been placed under house arrest and confined to an insane asylum, Sade was repeatedly jailed for his sexual misconduct and libertine dementia. It wasn’t until his incarceration that he began his literary career, at age 50.

*

Sade was born in 1740 to an aristocratic family and spent his late teens in the military. As a young man, Sade discovered that he not only liked rough sex—and pushing sensual experience to the extreme—but also the excitement of knowing he was committing a crime. He engaged in orgies and affairs, often disappearing for long periods while his wife was left alone with the children. And if he was often cruel, he became especially so to prostitutes who confessed to believing in the Church. “The idea of God is the sole wrong for which I cannot forgive mankind,” he wrote in one of his many novels.

At 23, not long after he married a young heiress, Sade procured the services of Mlle. Testard, a comely teenage prostitute who worked the outskirts of Paris. Sade asked Testard if she held religious convictions, and when she said she did, he harangued her with vile and degrading insults and masturbated into a chalice. He also called the Lord a “motherfucker” and inserted two communion hosts into the girl before violating her himself, all the while screaming “If thou art God, avenge thyself.”

He then asked her to heat a cat-o-nine-tails until it glowed red and to beat him with it. When she refused to let him beat her in reciprocation, he masturbated with two crucifixes, held her at knife-point, and forced her to repeat a litany of blasphemies. Scandal erupted immediately, but Sade avoided arrest by hiding out in his country chateau.

Other scandals would follow: one Easter morning Sade noticed Rose Kellor begging alms outside a church. Unemployed and desperate, Kellor agreed to work as a servant in Sade’s household. But when they arrived home, Sade became enraged and ripped off her clothes, throwing her on the bed face down, and assaulted her by whipping her backside until she bled. Her screams of terror only seemed to assist him in reaching climax, which caused Sade to scream in unison with her.

When the half-naked woman arrived at the police station covered in her own blood, it was the beginning of a furor that would ultimately lead to Sade’s arrest. His humiliated wife came to his assistance—as she often did—and bribed Kellor to drop the charges, but the police persisted and the affair resulted in years of legal problems for Sade.

Sade’s addiction to sexual deviance was such it seemed that nothing but jail could stop him. Forced by her husband’s many years in prison (along with her newfound religious zeal), Sade’s wife and protector finally abandoned him.

Shortly after the outbreak of the French Revolution, Sade was released from the Bastille, though not for his desperate lies shouted down to the street. Afterwards, he seemed to lead a quieter life. He involved himself in politics, representing his district of Paris, and for the most part avoided controversy (or assaulting women). He spent much of his twilight focused on what had sustained him in prison: literature. If prison offered no opportunity to titillate his senses with prostitutes, orgies, beatings, and blasphemous sex, then he would channel those fantasies into his novels and plays.

Though his writing style is reminiscent of Horatio Alger’s in its didactic handling of the pantheon of virtues, a Sadian novel or play (as differentiated from “sadistic"—though they were that, too) is anything but a rags-to-riches story. In fact, by observing each of ten traditional virtues Sade cites, the title character of Justine is abused and preyed upon by a conniving and opportunistic society —raped, brutalized, manipulated, robbed, tricked, molested. Sade’s work was graphic for its time, and one critic remarked that if Sade’s novels fell into the hands of soldiers, 20,000 women would be raped.

Sade died in 1814, buried as per his instructions in an unmarked grave that was allowed to grow wild. His influence would be immeasurable. Upon publishing Sade, Apollinaire declared that Sade’s writings would dominate the 20th Century. Henry Miller called Sade the most maligned, misunderstood figure in letters. In 1840, a full century after his birth, the word “sadism” entered the dictionary for the first time. The Encyclopedia Britannica defines sadism as a “psychosexual disorder in which sexual urges are gratified by the infliction of pain on another person.” It would be decades before “sadism” would be paired with “masochism,” although the two seem, at least in Sade’s example, bound inextricably today.

Sade repeatedly wrote that the more aware he was that his behavior was criminal the more it excited him. And ironically, in cases like Sade’s, the punishment that most inflicted psychological anguish as well as physical restrictions—i.e., that most punished Sade—was perhaps the best reward. If the confinement didn’t excite him like a good flogging, at least it helped spur something a little less fleeting than sensual pleasure, his writing life. But his wild life raises a paradox perhaps for the first time: How do you punish a masochist?

Originally published in Killing the Buddha