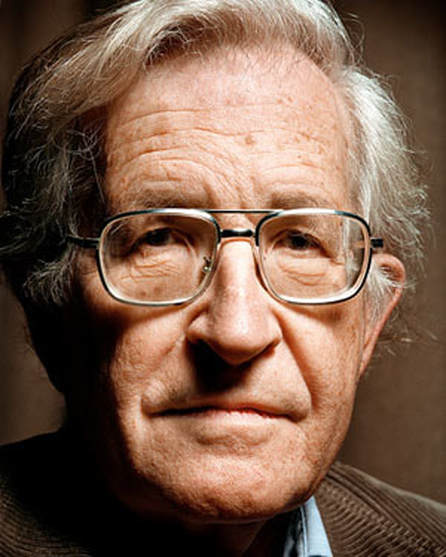

NOAM CHOMSKY HALF-FULL

Noam Chomsky discusses his forthcoming book, the hypocrisy of neoliberalism, where he feels hopeful about democracy despite U.S. terrorism, and his friendship—okay, passing acquaintance—with Hugo Chavez and other “pink tide” presidents.

If Noam Chomsky’s critics have a common refrain, it is pointing to his habit of being far too hard on America’s motives and too easy on its opponents. The former, of course, is his métier. The latter criticism has limited (though a few important) instances. In fact, Chomsky’s central question is how do you punish the crook who owns the jailhouse, pays the police their salaries, and fails consistently to see his crimes as such? Or perhaps, how do you get a self-enamored hypocrite to reckon with his pathology? Certainly not by repeating the praise, or what Chomsky sometimes calls America’s “state religion” of self-worship. And despite this, in a very limited way, Chomsky does give credit where credit is due.

In his forthcoming book Hopes and Prospects, Chomsky admits that a black family in the White House is historic. But he credits not “America,” a “system of power” defined by “market interventions” in the economy that once tolerated, and even fought for, the right to own humans as slaves. Nor does he give much credit to “Brand Obama,” as he calls the phenomenon that elected our new president, insisting that the new president is “likely to ‘have more influence on boardrooms than any president since Ronald Reagan.’” In fact, Chomsky gives credit for the 2008 election, in a way, to himself and his ilk.

In an early manuscript of the book, Chomsky writes, “The two candidates in the Democratic primary were a woman and an African-American. That, too, was historic. It would have been unimaginable forty years ago. The fact that the country has become civilized enough to accept this outcome is a considerable tribute to the activism of the nineteen sixties and its aftermath, with lessons for the future.” As such, this small tome is Chomsky’s legacy book.

And high time. His landmark critique of B.F. Skinner that crippled behaviorism’s predominance in psychology and linguistics turns fifty this year. His first book on politics, American Power and the New Mandarins: Historical and Political Essays, turns forty. The Essential Chomsky, edited by Anthony Arnove, came out from the New Press last year, in time for Chomsky’s eightieth birthday. And Chomsky’s wife died of cancer last winter, which would make anyone take stock. Regularly voted into the “top public intellectual” polls various magazines frequently run, the linguist and foreign policy critic, said to be worth two million dollars, remains a polarizing figure.

What’s remarkable is how Chomsky’s criticism of the Vietnam war and America’s many interventions seem even more relevant today, prescient in their understanding of how American greed, dehumanization of others, cultural ignorance, and hypocrisy are rewritten as pragmatic, not moral, mistakes. In “The Remaking of History,” from Toward a New Cold War: Essays on the Current Crisis and How We Got There, he writes, “They may concede the stupidity of American policy, and even its savagery, but not the illegitimacy inherent in the entire enterprise.” He continues a page later, “One may criticize the intellectual failure of planners, their moral failures, and even the generalized and abstract ‘will to exercise domination’ to which they have regrettably but understandably succumbed. But the principle that the United States may exercise force to guarantee a certain global order that will be ‘open’ to transnational corporations—that is beyond the bounds of polite discourse.”

Yet Chomsky has been criticized for accuracy and balance, for the petty (citing statements made by an “embassy” rather than “ambassador”) and the heinous (apologist for Pol Pot; a distortion, he insists, of his views), but most commonly, it seems, for comparing U.S. behavior to Hitler’s. In Prospect Magazine, Oliver Kamm writes of Chomsky’s early political writings as going “beyond the standard left critique of U.S. imperialism to the belief that ‘what is needed [in the US] is a kind of denazification.’” “This diagnosis,” Kamm continues, “is central to Chomsky’s political output. While he does not depict the U.S. as an overtly repressive society—instead, it is a place where ‘money and power are able to filter out the news fit to print and marginalize dissent’—he does liken America’s conduct to that of Nazi Germany. In his newly published Imperial Ambitions, he maintains that ‘the pretenses for the invasion [of Iraq] are no more convincing than Hitler’s.’”

On balance, Chomsky is a vital, even indispensable voice in the American cultural debate, needed to remind us of the outrage we should feel as the modernization of American life brings us to accept as necessary and understandable the devastation of foreign countries with little actual public debate and no input from the citizens of those countries. How do our presidents’ “terrorist” campaigns (in Chomsky’s terms) become a normal functioning of the state? How does a country that so readily welcomes outsiders, or purports to, so easily bury them by “overthrowing governments around the world and installing malicious dictatorships, assassinating people” or write them off as collateral damage? Perhaps we should, or do, on some level, share his outrage. And yet his voice has been every bit as ruthless, and occasionally selective (like most good rhetoricians), as his opponents suggest. Does that run counter to, or complement, the voice and methodology of the systems of power he criticizes?

—Joel Whitney for Guernica

Guernica: You’ve been savaging U.S. foreign policy for a long time. What’s new in Hopes and Prospects? Or would you say that you’re reworking a single thesis with new examples?

Noam Chomsky: There are new things that are happening. But I don’t think the basic principles of international affairs or social organization or aspirations for the future change very much. In fact, they haven’t for a long time.

Guernica: Does that imply that your approach as a critic isn’t effective?

Noam Chomsky: On the contrary, it has been quite effective in ways I have discussed repeatedly and at length, even though it hasn’t reached as far as changing fundamental principles and their institutional basis.

Guernica: One thing that never changes in your work is the meditation on the devastating effects of U.S. foreign policy. Here in the U.S., we endlessly tell ourselves, and our leaders especially do this, that “we’re good.” No matter the results, our intentions are good.

Noam Chomsky: Systems of power don’t have good intentions. You’ll occasionally in history find a benevolent dictator or a king who has the interests of the people at heart. But fundamentally, structures of power are not moral agents. We don’t look for good intentions. Of course, they all profess good intentions. But of course that’s also true of Hitler.

Guernica: Are “structures of power” amoral or immoral?

Noam Chomsky: Structures of power are amoral. The CEO, say, of the American Petroleum Institute may care a lot about whether his grandchildren will have a decent world to live in. But as CEO of the American Petroleum Institute, he’s going to try to make that impossible by doing what they’re doing right now, in fact. Working out ways to try to duplicate the success of the insurance industry in undermining any kind of health reform. They’ve already announced, “We’re gonna try to learn from [the health insurance industry’s] tactics and block any kind of energy or environmental bill.” Now he knows (he’s not an idiot) that could lead to a serious catastrophe which could undermine the prospects for the life of his grandchildren whom he cares a lot about. But as the director of a petroleum institute, he can’t consider that. If he did, he’d no longer have that position.

Guernica: You write about how corporations have these super-human rights and that investors and by-laws force them to take every advantage to maximize profits. But what you just said about structures of power being amoral, it seems to me that your work is actually asking them to be moral, no?

Noam Chomsky: I’m not addressing CEOs of corporations or President Obama or anything like that. I’m addressing people, saying, “Look, you’ve got a lot of opportunities. You can effect changes, which will change the actions of structures of power, which will in fact dissolve the structures of power.”

Guernica: What are those changes you mention above that can dissolve the structures of power?

Noam Chomsky: Consider the systematic dismantling of industrial capacity, say GM plants, destroying the workforce and communities, while Obama’s transportation secretary is abroad seeking to use federal stimulus money to contract with Spanish firms to provide high-speed transport—which could be produced by converting the plants that are being dismantled, by the skilled workforce being abandoned. It might require takeover of the facilities by “stakeholders”—workforce and community. There’s no economic principle that bars that, and it could happen with sufficient consciousness and popular support.

Guernica: One group you seem to expect a little more out of, by way of intermediaries between us people and the “power structures,” seems to be intellectuals. In the “Responsibility of—”

Noam Chomsky: The people we call intellectuals aren’t necessarily smarter or more knowledgeable than anyone else. But they happen to have a lot of privilege, and privilege confers responsibility. And so they oughta do things. I don’t expect them to.

Guernica: You’ve called “the inability of educated classes to perceive what they are doing” an “historical universal.”

Noam Chomsky: Close to it.

Guernica: And you cite a story in the New York Times where “the reviewer,” you write, “constitutional lawyer Noah Feldman, described Osama [bin Laden]’s descent to greater and greater evil over the years, finally reaching the absolute lower depths, when ‘he put forth the perverse claim that since the United States is a democracy, all citizens bear responsibility for its government’s actions, and civilians are therefore fair targets.’” What’s significant about this?

Noam Chomsky: What’s significant is what directly follows it. There had been an election in Palestine, actually the first really free election in the Arab world, and two days after Noah Feldman’s article appeared, Steven Erlanger on the front page of the New York Timesreported blandly that the U.S. government has just undertaken to punish the people of Palestine for voting the wrong way in a free election. Well, that makes Osama bin Laden look pretty tame. And these things appear right next to each other, and no one notices it.

Guernica: Am I right to believe that you essentially make no distinction between U.S. “terrorism,” i.e. interventions, and, say, al Qaeda’s terrorism?

Noam Chomsky: Yeah, U.S. terrorism is often far worse because it’s a powerful state. Take 9/11. That was a serious terrorist act. In Latin America, they often call it “the second 9/11” because there was another one, namely September 11, 1973.

Guernica: In Chile.

Noam Chomsky: Suppose that al Qaeda had not just blown up the World Trade Center, but suppose that they’d bombed the White House, killed the president, established a military dictatorship, killed maybe fifty to a hundred thousand people, maybe tortured seven hundred thousand, instituted a major international terrorist center in Washington, which was overthrowing governments around the world and installing malicious dictatorships, assassinating people, [and] brought in a bunch of economists who drove the economy into its worst disaster maybe in history. Well, that would be worse than what we call 9/11. And it did happen, namely on 9/11/1973. All that I’ve changed is per capita equivalence in numbers, a standard way to measure. Well, okay, that’s one we were responsible for. So yeah, it’s much worse.

Guernica: Some critics of U.S. foreign policy have been arguing for a universally accepted definition of terrorism to standardize in media, governments, etc.

Noam Chomsky: I agree. Reagan declared a war on terror in 1981—he said that’d be the core of our foreign policy. And since then, I’ve been writing about terrorism using the official definition in the U.S. code, and in Army manuals, and, in fact, in British law. It’s a pretty good definition. Now that’s considered outrageous. And the reason is when you use the official definition, it follows pretty quickly that the United States is a leading terrorist state. Now that’s the “wrong” conclusion, so therefore we can’t use that definition. There are academic conferences and sober volumes on terrorism trying to find some appropriate definition, and the “appropriate” definition has a very definite condition to meet. It has to include the terror that they carry out against us but exclude the terror that we carry out against them.

Guernica: True or false: no one did more to oppose the tyrannical communism of the Soviets?

Noam Chomsky: I don’t know what you mean by “tyrannical communism of the Soviets.” That was one particular form of tyranny, one that was out of U.S. control, and perceived as offering a model for others, so naturally the U.S. generally opposed it—though not when it was bearing the brunt of the war against the Nazis. The U.S. has also opposed democracies and repeatedly overthrew them and established tyrannies. And it supported, and still supports, brutal tyrannies. The question is misformulated and can’t be answered.

Guernica: Soviet communism—you don’t know what that is?

Noam Chomsky: I know what I think it is, and has been since 1918: the most severe attack on socialism/communism apart from fascism. What I don’t know is what you think it is.

Guernica: Your definition sounds fine. Utne characterized your work as having “an unflagging sense of outrage.” I’m wondering, when you diligently dissect exactly what your country has done in places like Chile, Vietnam, Iraq, and elsewhere, when you log numbers of innocent civilians killed, and carefully present these outrageous quotes from members of government or heads of corporations, what you’re feeling. I believe the anger comes through. What else is going on? Shame? Guilt?

Noam Chomsky: All of them. Shame and guilt, of course, because there’s much that we can do about it, that I haven’t done. And outrage because, yes, it’s outrageous. And disgust at the hypocrisy in which it’s veiled. But there’s no point in revealing those emotions. You know, maybe I can talk about them with my wife or something. But what’s the point of going public with them? Doesn’t do any good.

Guernica: Yet those emotions come through in your work as a subtext.

Noam Chomsky: Maybe. And it very much angers supporters of state violence; in fact, they’re infuriated by it, when it comes out.

Guernica: What do you mean?

Noam Chomsky: When it comes out, they are sometimes infuriated by it. I happened to be in England a couple of days ago [for] an interview at BBC. One of the things the interviewer brought up is a statement of mine showing how incomparably awful I am. The statement is “One has to ask whether what the United States needs is dissent or denazification.” And that’s so utterly outrageous; it shows I’m kind of a maniac from outer space. So I asked him what I always do when somebody brings it up. I said, “Did you read the context?” And of course he hadn’t. So I said, “Okay, here’s the context.” During the Vietnam War, the Chicago Museum of Science set up a diorama of a Vietnamese village in which children could be on the outside with guns and shoot into the village and try to kill people. And there was a protest by a group of mothers, a quiet protest, protesting this thing. There was an article in the New York Times condemning—not the exhibit, but the mothers—because they were trying to take away fun from the kiddies. And in that context I said, “Sometimes you have to wonder whether what’s needed is dissent or denazification.” I think it’s just the right thing to say.

Guernica: You’ve written how utterly Iraqis are excluded from the decisions made about their country…

Noam Chomsky: Or Vietnamese or Central Americans, or a long list of others. In fact, we don’t even care about them. If you listen to National Public Radio and happened to have it on last night (or maybe it was PBS), they were discussing the debates about what to do in Afghanistan. One of their correspondents was asked to comment on the costs of the war. She went through the costs of the war, so many hundreds of billions, and then the most severe cost—you know, a thousand American soldiers killed—and then the discussion ended. Now, is that the only cost? There’s no cost to Afghans?

Guernica: One of the ironic “hopes” in your book is the term “hope” as used by what you call “Brand Obama.” Brand Obama seemed to buttress Americans’ assumptions that because we elected a part-black president, we must be over our racism and this is more evidence that we have a noble purpose and a basic goodness. But you point to other countries, India, Bolivia—and where else?—where an outsider was elected.

Noam Chomsky: It’s happening in many parts of Latin America. Bolivia is particularly dramatic. But it’s also true in Brazil. Lula, the president of Brazil; he’s a peasant, steel worker, union organizer, didn’t have much higher education. What put him into power are these vast popular movements. They don’t go along with his policies altogether; by any means, they’re pretty critical of them. But part of the electoral base, like the Landless Workers’ Movement may be the most important mass popular movement in the world. The same is happening elsewhere. Comparing that with our system should lead us to a deal of introspection about just who and what we are.

Guernica: Are you and Hugo Chavez friends?

Noam Chomsky: We’ve met on a friendly basis, but I think you might ask yourself why you are asking this question, and not asking, for example, whether Lula, Correa, and others are friends (for the record, they are, to the same extent). I think we know the answers, but they might be useful for you to think about the matter more carefully.

Guernica: I am unaware of either of those others holding up one of your books and giving your sales a renewed jolt.

Noam Chomsky: It doesn’t answer my question. The fact that he held up my books says nothing about whether we are friends. We’ve never met. I’ve praised work of Hume’s, but it doesn’t mean he was my friend. The question arises about Chavez, not Lula (who I know a lot better) or Correa (who I just spent a few hours with) or many others who are at the heart of the “pink tide” because Chavez is demonized by state/media propaganda. I don’t accept that. Nor, I think, should you.

Guernica: You just said you have met him. Now you haven’t? Your reflexive antagonism aside, I’m happy to give you a moment to explain why we shouldn’t accept state/media propaganda against Chavez.

Noam Chomsky: I hadn’t met him when he held my book up at the UN. Since then, I did spend a few hours with him, like Correa, nothing like Lula, who I spent several days with and got to know pretty well. Sorry if it sounds like reflexive antagonism. It’s rather that I think we should be asking ourselves why the reflexive question is about Chavez—not Lula, or Correa, or for that matter Morales, who I haven’t met but have written about far more than Chavez.

Guernica: In the new book, you hit Obama pretty hard over his cabinet and the Wall Street types in his administration. You also basically allege that neoliberalism and the free market policies that we recommend to others—not only do we not follow them, but they don’t work, in terms of standard of living, wages, etc. You actually say protectionism does work and point to some interesting examples. Ronald Reagan. South Korea.

Noam Chomsky: Adam Smith had advice for the American colonies in the seventeen seventies. He advised the colonies to follow classical economic principles—they’re not very different from neoliberalism. In fact, it’s pretty much what economists today recommend to the third world. He said, Keep to your comparative advantages—the term “comparative advantage” hadn’t been invented yet—produce what you’re good at, which is catching fish, hunting fur, and growing food, and export it to us in England. And import superior British manufactures. But the U.S. gained its independence, so it didn’t have to follow that advice, and didn’t. It immediately set up under Alexander Hamilton high protective barriers to try to bar superior British textiles, in later years British steel. And it built up its own manufacturing base under protective barriers and by an enormous amount of state intervention. Take, say, cotton, the fuel of American industrialization. Well, how did America produce cotton? First of all, by exterminating the indigenous population. Secondly, by slavery. Those are pretty severe market interventions. Yeah, they worked.

Guernica: So your greater point is…

Noam Chomsky: I’m not recommending protectionism. I’m just saying, let’s be honest. Before we preach to others, let’s find out the truth about what we ourselves do. So take Ronald Reagan whom you mentioned. He’s considered the high priest of free markets. In fact, he was by far the most protectionist president in post-war U.S. history.

Guernica: So what are you recommending?

Noam Chomsky: I think decisions should be made in an entirely different manner for entirely different ends. Should producing more goods and consuming more goods be the highest value in life? That’s not obvious, by any means.

Guernica: And what would be?

Noam Chomsky: Living decent lives, in an environment that provides for people’s essential needs, offers them opportunities to become creative, active, to work together in solidarity, [and lead] more happy, creative lives. That’s a more important goal, I think.

Guernica: Here’s one critic of your work, Nick Cohen in the Observer: “The lesson of 11 September is that no constraints of morality or conscience would stop al-Qaeda exploding a nuclear weapon. If however, it is all our fault, as Chomsky says, perhaps we can avert catastrophe by being nicer and better people. Perhaps we can, but Chomsky is as reluctant to admit that al Qaeda is an autonomous movement as he is to admit the existence of the democratic and socialist opposition to Saddam Hussein.”

Noam Chomsky: They’re mentioning somebody with my name. But it doesn’t relate at all to anything I’ve ever said or believe. Who did you say you’re quoting?

Guernica: Nick Cohen in the Observer.

Noam Chomsky: Oh, Nick Cohen’s a maniac. If you’ll notice, he never cites anything. Does he cite anything? That already gives you the answer. Go back and check. He doesn’t cite anything. These are just diatribes, tantrums. I’m not interested in them.

Guernica: The greater point is that there are maniacs who have sought from their clerics and received permission to use nuclear weapons on civilians.

Noam Chomsky: Yes, there are. And we should try to prevent it. And there are ways to prevent it, and I discuss them, but they’re not his ways. His ways are just bomb everybody in sight. Well, I think that’s the way to increase terror. In fact, it has increased terror.

Guernica: It’s increased terror sevenfold, you write (citing analysts on the Iraq war).

Noam Chomsky: But he doesn’t like what I say, so he’ll scream and shout and slander. Why pay attention to him? Do you read Stalinist party acts?

Guernica: I don’t.

Noam Chomsky: Okay.

If Noam Chomsky’s critics have a common refrain, it is pointing to his habit of being far too hard on America’s motives and too easy on its opponents. The former, of course, is his métier. The latter criticism has limited (though a few important) instances. In fact, Chomsky’s central question is how do you punish the crook who owns the jailhouse, pays the police their salaries, and fails consistently to see his crimes as such? Or perhaps, how do you get a self-enamored hypocrite to reckon with his pathology? Certainly not by repeating the praise, or what Chomsky sometimes calls America’s “state religion” of self-worship. And despite this, in a very limited way, Chomsky does give credit where credit is due.

In his forthcoming book Hopes and Prospects, Chomsky admits that a black family in the White House is historic. But he credits not “America,” a “system of power” defined by “market interventions” in the economy that once tolerated, and even fought for, the right to own humans as slaves. Nor does he give much credit to “Brand Obama,” as he calls the phenomenon that elected our new president, insisting that the new president is “likely to ‘have more influence on boardrooms than any president since Ronald Reagan.’” In fact, Chomsky gives credit for the 2008 election, in a way, to himself and his ilk.

In an early manuscript of the book, Chomsky writes, “The two candidates in the Democratic primary were a woman and an African-American. That, too, was historic. It would have been unimaginable forty years ago. The fact that the country has become civilized enough to accept this outcome is a considerable tribute to the activism of the nineteen sixties and its aftermath, with lessons for the future.” As such, this small tome is Chomsky’s legacy book.

And high time. His landmark critique of B.F. Skinner that crippled behaviorism’s predominance in psychology and linguistics turns fifty this year. His first book on politics, American Power and the New Mandarins: Historical and Political Essays, turns forty. The Essential Chomsky, edited by Anthony Arnove, came out from the New Press last year, in time for Chomsky’s eightieth birthday. And Chomsky’s wife died of cancer last winter, which would make anyone take stock. Regularly voted into the “top public intellectual” polls various magazines frequently run, the linguist and foreign policy critic, said to be worth two million dollars, remains a polarizing figure.

What’s remarkable is how Chomsky’s criticism of the Vietnam war and America’s many interventions seem even more relevant today, prescient in their understanding of how American greed, dehumanization of others, cultural ignorance, and hypocrisy are rewritten as pragmatic, not moral, mistakes. In “The Remaking of History,” from Toward a New Cold War: Essays on the Current Crisis and How We Got There, he writes, “They may concede the stupidity of American policy, and even its savagery, but not the illegitimacy inherent in the entire enterprise.” He continues a page later, “One may criticize the intellectual failure of planners, their moral failures, and even the generalized and abstract ‘will to exercise domination’ to which they have regrettably but understandably succumbed. But the principle that the United States may exercise force to guarantee a certain global order that will be ‘open’ to transnational corporations—that is beyond the bounds of polite discourse.”

Yet Chomsky has been criticized for accuracy and balance, for the petty (citing statements made by an “embassy” rather than “ambassador”) and the heinous (apologist for Pol Pot; a distortion, he insists, of his views), but most commonly, it seems, for comparing U.S. behavior to Hitler’s. In Prospect Magazine, Oliver Kamm writes of Chomsky’s early political writings as going “beyond the standard left critique of U.S. imperialism to the belief that ‘what is needed [in the US] is a kind of denazification.’” “This diagnosis,” Kamm continues, “is central to Chomsky’s political output. While he does not depict the U.S. as an overtly repressive society—instead, it is a place where ‘money and power are able to filter out the news fit to print and marginalize dissent’—he does liken America’s conduct to that of Nazi Germany. In his newly published Imperial Ambitions, he maintains that ‘the pretenses for the invasion [of Iraq] are no more convincing than Hitler’s.’”

On balance, Chomsky is a vital, even indispensable voice in the American cultural debate, needed to remind us of the outrage we should feel as the modernization of American life brings us to accept as necessary and understandable the devastation of foreign countries with little actual public debate and no input from the citizens of those countries. How do our presidents’ “terrorist” campaigns (in Chomsky’s terms) become a normal functioning of the state? How does a country that so readily welcomes outsiders, or purports to, so easily bury them by “overthrowing governments around the world and installing malicious dictatorships, assassinating people” or write them off as collateral damage? Perhaps we should, or do, on some level, share his outrage. And yet his voice has been every bit as ruthless, and occasionally selective (like most good rhetoricians), as his opponents suggest. Does that run counter to, or complement, the voice and methodology of the systems of power he criticizes?

—Joel Whitney for Guernica

Guernica: You’ve been savaging U.S. foreign policy for a long time. What’s new in Hopes and Prospects? Or would you say that you’re reworking a single thesis with new examples?

Noam Chomsky: There are new things that are happening. But I don’t think the basic principles of international affairs or social organization or aspirations for the future change very much. In fact, they haven’t for a long time.

Guernica: Does that imply that your approach as a critic isn’t effective?

Noam Chomsky: On the contrary, it has been quite effective in ways I have discussed repeatedly and at length, even though it hasn’t reached as far as changing fundamental principles and their institutional basis.

Guernica: One thing that never changes in your work is the meditation on the devastating effects of U.S. foreign policy. Here in the U.S., we endlessly tell ourselves, and our leaders especially do this, that “we’re good.” No matter the results, our intentions are good.

Noam Chomsky: Systems of power don’t have good intentions. You’ll occasionally in history find a benevolent dictator or a king who has the interests of the people at heart. But fundamentally, structures of power are not moral agents. We don’t look for good intentions. Of course, they all profess good intentions. But of course that’s also true of Hitler.

Guernica: Are “structures of power” amoral or immoral?

Noam Chomsky: Structures of power are amoral. The CEO, say, of the American Petroleum Institute may care a lot about whether his grandchildren will have a decent world to live in. But as CEO of the American Petroleum Institute, he’s going to try to make that impossible by doing what they’re doing right now, in fact. Working out ways to try to duplicate the success of the insurance industry in undermining any kind of health reform. They’ve already announced, “We’re gonna try to learn from [the health insurance industry’s] tactics and block any kind of energy or environmental bill.” Now he knows (he’s not an idiot) that could lead to a serious catastrophe which could undermine the prospects for the life of his grandchildren whom he cares a lot about. But as the director of a petroleum institute, he can’t consider that. If he did, he’d no longer have that position.

Guernica: You write about how corporations have these super-human rights and that investors and by-laws force them to take every advantage to maximize profits. But what you just said about structures of power being amoral, it seems to me that your work is actually asking them to be moral, no?

Noam Chomsky: I’m not addressing CEOs of corporations or President Obama or anything like that. I’m addressing people, saying, “Look, you’ve got a lot of opportunities. You can effect changes, which will change the actions of structures of power, which will in fact dissolve the structures of power.”

Guernica: What are those changes you mention above that can dissolve the structures of power?

Noam Chomsky: Consider the systematic dismantling of industrial capacity, say GM plants, destroying the workforce and communities, while Obama’s transportation secretary is abroad seeking to use federal stimulus money to contract with Spanish firms to provide high-speed transport—which could be produced by converting the plants that are being dismantled, by the skilled workforce being abandoned. It might require takeover of the facilities by “stakeholders”—workforce and community. There’s no economic principle that bars that, and it could happen with sufficient consciousness and popular support.

Guernica: One group you seem to expect a little more out of, by way of intermediaries between us people and the “power structures,” seems to be intellectuals. In the “Responsibility of—”

Noam Chomsky: The people we call intellectuals aren’t necessarily smarter or more knowledgeable than anyone else. But they happen to have a lot of privilege, and privilege confers responsibility. And so they oughta do things. I don’t expect them to.

Guernica: You’ve called “the inability of educated classes to perceive what they are doing” an “historical universal.”

Noam Chomsky: Close to it.

Guernica: And you cite a story in the New York Times where “the reviewer,” you write, “constitutional lawyer Noah Feldman, described Osama [bin Laden]’s descent to greater and greater evil over the years, finally reaching the absolute lower depths, when ‘he put forth the perverse claim that since the United States is a democracy, all citizens bear responsibility for its government’s actions, and civilians are therefore fair targets.’” What’s significant about this?

Noam Chomsky: What’s significant is what directly follows it. There had been an election in Palestine, actually the first really free election in the Arab world, and two days after Noah Feldman’s article appeared, Steven Erlanger on the front page of the New York Timesreported blandly that the U.S. government has just undertaken to punish the people of Palestine for voting the wrong way in a free election. Well, that makes Osama bin Laden look pretty tame. And these things appear right next to each other, and no one notices it.

Guernica: Am I right to believe that you essentially make no distinction between U.S. “terrorism,” i.e. interventions, and, say, al Qaeda’s terrorism?

Noam Chomsky: Yeah, U.S. terrorism is often far worse because it’s a powerful state. Take 9/11. That was a serious terrorist act. In Latin America, they often call it “the second 9/11” because there was another one, namely September 11, 1973.

Guernica: In Chile.

Noam Chomsky: Suppose that al Qaeda had not just blown up the World Trade Center, but suppose that they’d bombed the White House, killed the president, established a military dictatorship, killed maybe fifty to a hundred thousand people, maybe tortured seven hundred thousand, instituted a major international terrorist center in Washington, which was overthrowing governments around the world and installing malicious dictatorships, assassinating people, [and] brought in a bunch of economists who drove the economy into its worst disaster maybe in history. Well, that would be worse than what we call 9/11. And it did happen, namely on 9/11/1973. All that I’ve changed is per capita equivalence in numbers, a standard way to measure. Well, okay, that’s one we were responsible for. So yeah, it’s much worse.

Guernica: Some critics of U.S. foreign policy have been arguing for a universally accepted definition of terrorism to standardize in media, governments, etc.

Noam Chomsky: I agree. Reagan declared a war on terror in 1981—he said that’d be the core of our foreign policy. And since then, I’ve been writing about terrorism using the official definition in the U.S. code, and in Army manuals, and, in fact, in British law. It’s a pretty good definition. Now that’s considered outrageous. And the reason is when you use the official definition, it follows pretty quickly that the United States is a leading terrorist state. Now that’s the “wrong” conclusion, so therefore we can’t use that definition. There are academic conferences and sober volumes on terrorism trying to find some appropriate definition, and the “appropriate” definition has a very definite condition to meet. It has to include the terror that they carry out against us but exclude the terror that we carry out against them.

Guernica: True or false: no one did more to oppose the tyrannical communism of the Soviets?

Noam Chomsky: I don’t know what you mean by “tyrannical communism of the Soviets.” That was one particular form of tyranny, one that was out of U.S. control, and perceived as offering a model for others, so naturally the U.S. generally opposed it—though not when it was bearing the brunt of the war against the Nazis. The U.S. has also opposed democracies and repeatedly overthrew them and established tyrannies. And it supported, and still supports, brutal tyrannies. The question is misformulated and can’t be answered.

Guernica: Soviet communism—you don’t know what that is?

Noam Chomsky: I know what I think it is, and has been since 1918: the most severe attack on socialism/communism apart from fascism. What I don’t know is what you think it is.

Guernica: Your definition sounds fine. Utne characterized your work as having “an unflagging sense of outrage.” I’m wondering, when you diligently dissect exactly what your country has done in places like Chile, Vietnam, Iraq, and elsewhere, when you log numbers of innocent civilians killed, and carefully present these outrageous quotes from members of government or heads of corporations, what you’re feeling. I believe the anger comes through. What else is going on? Shame? Guilt?

Noam Chomsky: All of them. Shame and guilt, of course, because there’s much that we can do about it, that I haven’t done. And outrage because, yes, it’s outrageous. And disgust at the hypocrisy in which it’s veiled. But there’s no point in revealing those emotions. You know, maybe I can talk about them with my wife or something. But what’s the point of going public with them? Doesn’t do any good.

Guernica: Yet those emotions come through in your work as a subtext.

Noam Chomsky: Maybe. And it very much angers supporters of state violence; in fact, they’re infuriated by it, when it comes out.

Guernica: What do you mean?

Noam Chomsky: When it comes out, they are sometimes infuriated by it. I happened to be in England a couple of days ago [for] an interview at BBC. One of the things the interviewer brought up is a statement of mine showing how incomparably awful I am. The statement is “One has to ask whether what the United States needs is dissent or denazification.” And that’s so utterly outrageous; it shows I’m kind of a maniac from outer space. So I asked him what I always do when somebody brings it up. I said, “Did you read the context?” And of course he hadn’t. So I said, “Okay, here’s the context.” During the Vietnam War, the Chicago Museum of Science set up a diorama of a Vietnamese village in which children could be on the outside with guns and shoot into the village and try to kill people. And there was a protest by a group of mothers, a quiet protest, protesting this thing. There was an article in the New York Times condemning—not the exhibit, but the mothers—because they were trying to take away fun from the kiddies. And in that context I said, “Sometimes you have to wonder whether what’s needed is dissent or denazification.” I think it’s just the right thing to say.

Guernica: You’ve written how utterly Iraqis are excluded from the decisions made about their country…

Noam Chomsky: Or Vietnamese or Central Americans, or a long list of others. In fact, we don’t even care about them. If you listen to National Public Radio and happened to have it on last night (or maybe it was PBS), they were discussing the debates about what to do in Afghanistan. One of their correspondents was asked to comment on the costs of the war. She went through the costs of the war, so many hundreds of billions, and then the most severe cost—you know, a thousand American soldiers killed—and then the discussion ended. Now, is that the only cost? There’s no cost to Afghans?

Guernica: One of the ironic “hopes” in your book is the term “hope” as used by what you call “Brand Obama.” Brand Obama seemed to buttress Americans’ assumptions that because we elected a part-black president, we must be over our racism and this is more evidence that we have a noble purpose and a basic goodness. But you point to other countries, India, Bolivia—and where else?—where an outsider was elected.

Noam Chomsky: It’s happening in many parts of Latin America. Bolivia is particularly dramatic. But it’s also true in Brazil. Lula, the president of Brazil; he’s a peasant, steel worker, union organizer, didn’t have much higher education. What put him into power are these vast popular movements. They don’t go along with his policies altogether; by any means, they’re pretty critical of them. But part of the electoral base, like the Landless Workers’ Movement may be the most important mass popular movement in the world. The same is happening elsewhere. Comparing that with our system should lead us to a deal of introspection about just who and what we are.

Guernica: Are you and Hugo Chavez friends?

Noam Chomsky: We’ve met on a friendly basis, but I think you might ask yourself why you are asking this question, and not asking, for example, whether Lula, Correa, and others are friends (for the record, they are, to the same extent). I think we know the answers, but they might be useful for you to think about the matter more carefully.

Guernica: I am unaware of either of those others holding up one of your books and giving your sales a renewed jolt.

Noam Chomsky: It doesn’t answer my question. The fact that he held up my books says nothing about whether we are friends. We’ve never met. I’ve praised work of Hume’s, but it doesn’t mean he was my friend. The question arises about Chavez, not Lula (who I know a lot better) or Correa (who I just spent a few hours with) or many others who are at the heart of the “pink tide” because Chavez is demonized by state/media propaganda. I don’t accept that. Nor, I think, should you.

Guernica: You just said you have met him. Now you haven’t? Your reflexive antagonism aside, I’m happy to give you a moment to explain why we shouldn’t accept state/media propaganda against Chavez.

Noam Chomsky: I hadn’t met him when he held my book up at the UN. Since then, I did spend a few hours with him, like Correa, nothing like Lula, who I spent several days with and got to know pretty well. Sorry if it sounds like reflexive antagonism. It’s rather that I think we should be asking ourselves why the reflexive question is about Chavez—not Lula, or Correa, or for that matter Morales, who I haven’t met but have written about far more than Chavez.

Guernica: In the new book, you hit Obama pretty hard over his cabinet and the Wall Street types in his administration. You also basically allege that neoliberalism and the free market policies that we recommend to others—not only do we not follow them, but they don’t work, in terms of standard of living, wages, etc. You actually say protectionism does work and point to some interesting examples. Ronald Reagan. South Korea.

Noam Chomsky: Adam Smith had advice for the American colonies in the seventeen seventies. He advised the colonies to follow classical economic principles—they’re not very different from neoliberalism. In fact, it’s pretty much what economists today recommend to the third world. He said, Keep to your comparative advantages—the term “comparative advantage” hadn’t been invented yet—produce what you’re good at, which is catching fish, hunting fur, and growing food, and export it to us in England. And import superior British manufactures. But the U.S. gained its independence, so it didn’t have to follow that advice, and didn’t. It immediately set up under Alexander Hamilton high protective barriers to try to bar superior British textiles, in later years British steel. And it built up its own manufacturing base under protective barriers and by an enormous amount of state intervention. Take, say, cotton, the fuel of American industrialization. Well, how did America produce cotton? First of all, by exterminating the indigenous population. Secondly, by slavery. Those are pretty severe market interventions. Yeah, they worked.

Guernica: So your greater point is…

Noam Chomsky: I’m not recommending protectionism. I’m just saying, let’s be honest. Before we preach to others, let’s find out the truth about what we ourselves do. So take Ronald Reagan whom you mentioned. He’s considered the high priest of free markets. In fact, he was by far the most protectionist president in post-war U.S. history.

Guernica: So what are you recommending?

Noam Chomsky: I think decisions should be made in an entirely different manner for entirely different ends. Should producing more goods and consuming more goods be the highest value in life? That’s not obvious, by any means.

Guernica: And what would be?

Noam Chomsky: Living decent lives, in an environment that provides for people’s essential needs, offers them opportunities to become creative, active, to work together in solidarity, [and lead] more happy, creative lives. That’s a more important goal, I think.

Guernica: Here’s one critic of your work, Nick Cohen in the Observer: “The lesson of 11 September is that no constraints of morality or conscience would stop al-Qaeda exploding a nuclear weapon. If however, it is all our fault, as Chomsky says, perhaps we can avert catastrophe by being nicer and better people. Perhaps we can, but Chomsky is as reluctant to admit that al Qaeda is an autonomous movement as he is to admit the existence of the democratic and socialist opposition to Saddam Hussein.”

Noam Chomsky: They’re mentioning somebody with my name. But it doesn’t relate at all to anything I’ve ever said or believe. Who did you say you’re quoting?

Guernica: Nick Cohen in the Observer.

Noam Chomsky: Oh, Nick Cohen’s a maniac. If you’ll notice, he never cites anything. Does he cite anything? That already gives you the answer. Go back and check. He doesn’t cite anything. These are just diatribes, tantrums. I’m not interested in them.

Guernica: The greater point is that there are maniacs who have sought from their clerics and received permission to use nuclear weapons on civilians.

Noam Chomsky: Yes, there are. And we should try to prevent it. And there are ways to prevent it, and I discuss them, but they’re not his ways. His ways are just bomb everybody in sight. Well, I think that’s the way to increase terror. In fact, it has increased terror.

Guernica: It’s increased terror sevenfold, you write (citing analysts on the Iraq war).

Noam Chomsky: But he doesn’t like what I say, so he’ll scream and shout and slander. Why pay attention to him? Do you read Stalinist party acts?

Guernica: I don’t.

Noam Chomsky: Okay.