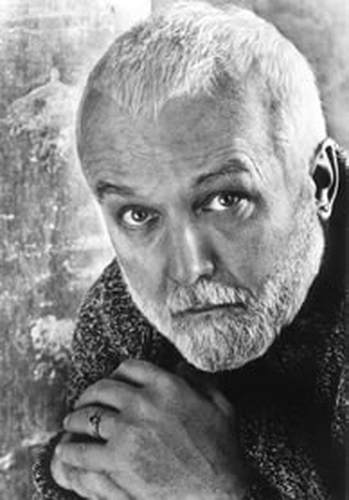

TELLING DETAILS: RUSSELL BANKS

Banks discusses his time in Students for a Democratic Society, finding a narrator's voice, and his (brief) acting career.

In Russell Banks’s latest book, The Darling, Hannah Musgrave hails from a wealthy, liberal New England family, but goes underground in the 1960s with a quasi-terror cell of Weatherman. She winds up thousands of miles away in Liberia, where she marries a government functionary and bears his children. Through her marriage Hannah comes to know Charles Taylor and other key figures in Liberia’s struggles to define itself. When full-on war erupts, Hannah is forced to flee her adopted land, leaving her family and taking with her a feeling of guilt, which underlies her retelling.

Banks is the author of the novels Rule of the Bone, Continental Drift, Affliction, and The Sweet Hereafter, which was made into an acclaimed film by director Atom Egoyan. Banks’ novel Cloudsplitter is being adapted for HBO.

I spoke with Banks by phone from his studio in the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York, where he lives with his wife, the poet Chase Twichell, and works in a converted “sugar shack.” He speaks of his work calmly, in measured tones, and frequently erupts into an ebullient laughter. Of his work and stature in American letters, The Village Voice writes, Russell Banks has now become “the most important living white male American on the official literary map, a writer we, as readers and writers, can actually learn from, whose books help and urge us to change.”

The Darling comes out in paperback on October 11.

—Joel Whitney

Guernica: Your characters often go on a journey, starting out as idealists and arriving somewhere else--

Russell Banks: (laughs) Someplace they never intended to go. Yeah.

Guernica: And in Hannah Musgrave’s case it involves some violence…

Russell Banks: Yeah, you know—but at the same time I’m not trying to judge or put down that kind of idealism, that love of justice or equality that drives people like Hannah and her cohort. So it’s not idea-driven or political—it’s not ideological in that sense. Ultimately I’m a novelist and storyteller and so I’m interested in character and contradictions of character and complexities of character.

Guernica: Hannah is certainly a complex character. Both your books, Cloudsplitter and The Darling, seem to have this exploration of class and race. Hannah seems at best ambivalent on both of those questions. Does she have tendencies toward racism?

Russell Banks: She has—she’s a white privileged person raised in an oppressive racist society and the higher you get up in the hierarchy of race and class the more difficult it is to scrape away. She’s engaged in that struggle. She’s attempting to deal with her own racism. And classism. But it ain’t simple, you know. Because it reinforces itself when you have the racial privilege and class privilege and she has both.

Guernica: She also talks about trying to cast off the influences of her parents… In a sense she seems to be using all of her affiliations to escape her childhood, her class--

Russell Banks: Yeah, there’s a mix of motives for every act we undertake, especially when we’re talking about the arc of a person’s life. So, sure, there’s a psychological or familial ground for her actions. There’s also an historical context for her. She’s born at a certain time with a particular social crisis in the 1960s and early 70s, so there’s that too. And there’s a cultural context for her as well. She’s from a liberal progressive family in the northeastern United States, idealistic—as she’s been raised that way. All these different factors come into play.

Guernica: Tell me a little about writing after 9/11 and writing a character like Hannah, who has ties to terrorism and sabotage cells.

Russell Banks: I wouldn’t have written this book before 9/11. One of the reasons that the book is framed by 9/11 is because Hannah’s life up till that moment couldn’t be lived after 9/11. For one thing, the security apparatus that has been established wouldn’t permit it—she couldn’t travel the way she travels on phony passports and IDs and so forth. She couldn’t live underground the way she has in the past.

Guernica: What drew you to Liberia?

Russell Banks: I got there through research that I did for Cloudsplitter, a novel based on the life of John Brown, because I had to learn a lot about the early abolitionist movement. I was intrigued by the creation of Liberia—the whole movement there of the American Colonization Society which was set up in the 1820s basically to send freed slaves back to Africa. It was one of those things which began at least in appearances as a benign, even benevolent, act which underneath was self-serving and ultimately cruel. I got very intrigued by that.

The more I examined it the more it seemed to express the theme of the unintended consequences of good intentions that seems to run throughout American history and even into the present, including the war in Iraq. And the Vietnam war. And that tied into Hannah Musgrave as she was sort of evolving in my mind.

Guernica: You said in a Salon interview that “I think in a sense a good novelist has to go to the emotional life that you had at different points in your life and access that.” What did that entail as you sketched out Hannah?

Russell Banks: That’s a good question. I haven’t really thought about it, to be honest with you (laughing), in terms of Hannah. I’m not sure when I made that comment but it may have had more to do with Rule of the Bone

Guernica: Yeah, it was 1998.

Russell Banks: Yeah, in a way I did have to go to my own emotional life in the 60s and early 70s and remember how angry I was. I mean my own reaction to the Vietnam War particularly, but also the racism in American society and the way it was being carried out in that era, in the context of the Vietnam War, was really very deep, and my reaction to it was one of anger and frustration and pessimism. I didn’t join Weatherman or anything but I did join Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). I found a chapter at Chapel Hill where I went to school, and so I came up to the edge of where Hannah went and she kept going. And friends of mine did keep going. But it wasn’t hard for me to get back to how angry we were back then in all kinds of ways. And also how strangely optimistic we were at times too, believing that we could actually effect change. Coming out of the Civil Rights movement, partly out of our youth and naivete in many ways, we were optimistic and did believe we could change society, and not just at the edges. But we found out later we couldn’t. But of course at the time, that was not how it seemed. But yeah, I did go back to my own emotional state.

Guernica: In the same interview you said, “So much of the American dream is used to manipulate people into putting themselves at risk and bending themselves all out of shape in order to chase that dream.” Hannah says she’s just hoping, at this point, to break even, to have as many good things as bad things happen in her life. She calls it a “zero-sum game.” Does she rank as one of your more pessimistic, optimistic, or realistic characters?

Russell Banks: (laughs) That’s very late in her game when she says that, too. She realizes she’ll be very lucky if she comes out at zero. She doesn’t speak for me, of course. No character, really—or rarely—speaks for the author. No one wants to end up historically in the same place they started. No one wants to have to repeat history over and over again. That’s too ugly. So you hope and I certainly hope that there’s a kind of evolution going on historically so that we don’t have to repeat everything horrible that has gone on. I wouldn’t say that I’m particularly optimistic about that. But I do know—I’m old enough now to remember a time in the United States when racism was much more dangerous and cruel and pervasive than it is today. It still exists but it was much more overt and structural than today. And I can remember a period in the country when it was much more difficult to be a woman than it is today. My full-grown daughters’ lives are different from their mother’s and certainly very different from their grandmothers’. So there is change. Would I call it progress? I guess we should call it progress.

Guernica: John Kerry makes a little cameo in a letter from Hannah’s parents.

Russell Banks: (laughing) Yeah, that was before the election, too, when I wrote that.

Guernica: Some of the historical figures of Liberia make appearances. Talk to me about these attempts to wedge fictional characters up against historical events and characters that we see both in Cloudsplitter and The Darling.

Russell Banks: Right. Well, there’s several different uses I suppose for historical characters. In the case of John Kerry, that’s almost like a telling detail to identify the class and the sort of social milieu of the parents. He’s useful because he’s associated with Vietnam Veterans Against the War, as we all now know after the election. But in my mind—I knew him actually in the middle 1970s, and I thought he was a very brave man and a very idealistic man at that time. And we know what he became, a sort of middle of the road, ordinary, flatfooted politician. And unctuous and self-righteous. But as a young man he was quite different. So I was just trying to get at that shift in time and so on as well. Then there’s the use of characters like Charles Taylor and Samuel Doe. Once you accept that you’re writing about a historical period and politically identifiable place like Liberia—if I was making up a place like Liberia it would be different, but if I’m really writing about Liberia—then those known historical figures have to be in the story. In some way or other. And in a small country like Liberia, it’s not hard for someone like Hannah, who’s married to someone in government, to get close to those figures. So, it’s plausibility, I suppose, is the other use for historical characters. The same could be said of Cloudsplitter. Along with John Brown are people like Emerson—and they have to appear among the cast, these known figures.

Guernica: Tell me about your process a little, starting with preparation and research. Did you go to Africa, for instance?

Russell Banks: I went to West Africa. I tried to get into Liberia actually, before I finished the book up. I did an awful lot of prep work beforehand, library, reading, talking to people who had spent time there, Peace Corps volunteers, Liberians living in the United States and so on. I even spent an entire weekend with an old CIA hand who’d been stationed in Liberia. So I went over trying to get in, just as I was finishing the book. Really what a novelist goes after is not what a journalist or scholar or historian would. I just wanted to get on the ground and see what it smells like. Or sounds like. You know, taste the food, that sort of thing. And I couldn’t get in because the country had exploded again in violence. And bodies were piling up in the streets of Monrovia, and people were running around firing Kalishnikovs in the air. And the roads were ordered closed, and there was no way to get in. And I thought, well, you know, I’m of an age where I really shouldn’t be doing this, so I stopped at the border. But it turns out I got it well enough right, I think. In fact, last night I was just having dinner and a young man sitting next to me recognized me and had just read the book. He also just got back from ten months in Liberia for an NGO there and was sort of shocked that I hadn’t been there. He’d read it as a road map. It was exact as far as he could see. And then I had Liberians living in the states come to me and say it was a fully accurate picture, and I felt ok about it.

Guernica: Then what’s the process like once you start writing? Do you have a set time when you like to write?

Russell Banks: I work in the mornings. I have a little studio about 200 yards from the house. It’s a renovated old sugar shack once used to water down maple sap into maple syrup, and usually I’m here in the mornings and I work until early afternoon.

Guernica: Tell me a little bit about how you establish a character’s voice?

Russell Banks: Well, the first thing is to establish who the narrator is talking to. Because we all speak differently depending on who we’re talking to. And we leave certain things out and other things in, and we use a different level of diction and our grammar even changes. In Hannah’s case, I decided that she was talking to a man and not a woman. And in my mind it had to be one person, because if you try to speak to more than one person you tend to get vaguer and vaguer. I just imagined she was talking to someone about her age, a man, a white man, a man with some of her experiences and beliefs, but by no means all of them, and it was a neighbor or someone who knew her well—though not a spouse—and so that pretty much described myself (laughs). So I just imagined that I was sitting next to her on her porch the entire summer and she was telling me her story—right here in the town that I live in. Once I had that established in my mind, then it wasn’t difficult to hear her voice, and let her speak. I don’t think of the process as an act of ventriloquism, or speaking through the characters at all. Of course, I’m the one setting the words down on the page. But I’m setting down what I think I hear in my ear.

Guernica: I was fortunate enough to interview your wife once [the poet Chase Twichell] who told me that poetry goes where prose can’t. Do you want to take issue with that?

Russell Banks: (laughs) No, I think she’s right. Having written poetry when I was younger and even occasionally now—the reason being exactly that. It goes to… it’s non-linear, and can be more so than prose. The expectations that we bring to a novel, essay or short story, or even to a sentence, those expectations are very different than what we bring to the line in verse. We simply allow ourselves to be taken somewhere else. It isn’t about language so much as it’s about structure and form and the expectation that the reader brings to it. So, I would agree with her.

Guernica: Good. I wouldn’t want to start anything between--

Russell Banks: No, you wouldn’t start anything.

Guernica: The process of turning your novels into films—has that gone smoothly for you?

Russell Banks: I wouldn’t say altogether smoothly, but it has gone well. I’ve had two adaptations that turned out well, Affliction and The Sweet Hereafter. And I’m working on—when you called I’m sitting here working on about the tenth revision for the script for Continental Drift, which we’re hoping to shoot in February and March of this year coming up. And I’m very happy about it at this point. At the end of the year, I might not be.

Guernica: Do you expect this to lead to another cameo? Is this the end of Russell Banks the writer and beginning of your acting career?

Russell Banks: I don’t think I have the right temperament for an actor. It’s really boring actually. I don’t think I’m very good at it. So I don’t think so.

Guernica: Is there a filmmaker you’d like to work with you haven’t had the chance to yet?

Russell Banks: I’d love to work with Gus van Sant. I admire what he does. Yeah, there’s a lot of filmmakers out there. I’ve been lucky with the ones I have worked with, starting with Atom Egoyan and Paul Schrader and now working with Rauol Peck, a Haitian French director on Continental Drift and Philip Kaufman who directed The Darling—I’ve been very lucky. I think what it is is the people who would be attracted to my books and want to make them movies tend not to be the big studio directors but rather independent-minded and artistically ambitious filmmakers.

Guernica: After this next screenplay, what’s next?

Russell Banks: I’ve been working on a novel most of this year off and on. I can’t say too much about it, but I know it’s set in the year 1936 and set up here in the Adirondacks.

Guernica: It won’t require any attempts to sneak into a war zone?

Russell Banks: No, I don’t think so (laughs). I hope not.

In Russell Banks’s latest book, The Darling, Hannah Musgrave hails from a wealthy, liberal New England family, but goes underground in the 1960s with a quasi-terror cell of Weatherman. She winds up thousands of miles away in Liberia, where she marries a government functionary and bears his children. Through her marriage Hannah comes to know Charles Taylor and other key figures in Liberia’s struggles to define itself. When full-on war erupts, Hannah is forced to flee her adopted land, leaving her family and taking with her a feeling of guilt, which underlies her retelling.

Banks is the author of the novels Rule of the Bone, Continental Drift, Affliction, and The Sweet Hereafter, which was made into an acclaimed film by director Atom Egoyan. Banks’ novel Cloudsplitter is being adapted for HBO.

I spoke with Banks by phone from his studio in the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York, where he lives with his wife, the poet Chase Twichell, and works in a converted “sugar shack.” He speaks of his work calmly, in measured tones, and frequently erupts into an ebullient laughter. Of his work and stature in American letters, The Village Voice writes, Russell Banks has now become “the most important living white male American on the official literary map, a writer we, as readers and writers, can actually learn from, whose books help and urge us to change.”

The Darling comes out in paperback on October 11.

—Joel Whitney

Guernica: Your characters often go on a journey, starting out as idealists and arriving somewhere else--

Russell Banks: (laughs) Someplace they never intended to go. Yeah.

Guernica: And in Hannah Musgrave’s case it involves some violence…

Russell Banks: Yeah, you know—but at the same time I’m not trying to judge or put down that kind of idealism, that love of justice or equality that drives people like Hannah and her cohort. So it’s not idea-driven or political—it’s not ideological in that sense. Ultimately I’m a novelist and storyteller and so I’m interested in character and contradictions of character and complexities of character.

Guernica: Hannah is certainly a complex character. Both your books, Cloudsplitter and The Darling, seem to have this exploration of class and race. Hannah seems at best ambivalent on both of those questions. Does she have tendencies toward racism?

Russell Banks: She has—she’s a white privileged person raised in an oppressive racist society and the higher you get up in the hierarchy of race and class the more difficult it is to scrape away. She’s engaged in that struggle. She’s attempting to deal with her own racism. And classism. But it ain’t simple, you know. Because it reinforces itself when you have the racial privilege and class privilege and she has both.

Guernica: She also talks about trying to cast off the influences of her parents… In a sense she seems to be using all of her affiliations to escape her childhood, her class--

Russell Banks: Yeah, there’s a mix of motives for every act we undertake, especially when we’re talking about the arc of a person’s life. So, sure, there’s a psychological or familial ground for her actions. There’s also an historical context for her. She’s born at a certain time with a particular social crisis in the 1960s and early 70s, so there’s that too. And there’s a cultural context for her as well. She’s from a liberal progressive family in the northeastern United States, idealistic—as she’s been raised that way. All these different factors come into play.

Guernica: Tell me a little about writing after 9/11 and writing a character like Hannah, who has ties to terrorism and sabotage cells.

Russell Banks: I wouldn’t have written this book before 9/11. One of the reasons that the book is framed by 9/11 is because Hannah’s life up till that moment couldn’t be lived after 9/11. For one thing, the security apparatus that has been established wouldn’t permit it—she couldn’t travel the way she travels on phony passports and IDs and so forth. She couldn’t live underground the way she has in the past.

Guernica: What drew you to Liberia?

Russell Banks: I got there through research that I did for Cloudsplitter, a novel based on the life of John Brown, because I had to learn a lot about the early abolitionist movement. I was intrigued by the creation of Liberia—the whole movement there of the American Colonization Society which was set up in the 1820s basically to send freed slaves back to Africa. It was one of those things which began at least in appearances as a benign, even benevolent, act which underneath was self-serving and ultimately cruel. I got very intrigued by that.

The more I examined it the more it seemed to express the theme of the unintended consequences of good intentions that seems to run throughout American history and even into the present, including the war in Iraq. And the Vietnam war. And that tied into Hannah Musgrave as she was sort of evolving in my mind.

Guernica: You said in a Salon interview that “I think in a sense a good novelist has to go to the emotional life that you had at different points in your life and access that.” What did that entail as you sketched out Hannah?

Russell Banks: That’s a good question. I haven’t really thought about it, to be honest with you (laughing), in terms of Hannah. I’m not sure when I made that comment but it may have had more to do with Rule of the Bone

Guernica: Yeah, it was 1998.

Russell Banks: Yeah, in a way I did have to go to my own emotional life in the 60s and early 70s and remember how angry I was. I mean my own reaction to the Vietnam War particularly, but also the racism in American society and the way it was being carried out in that era, in the context of the Vietnam War, was really very deep, and my reaction to it was one of anger and frustration and pessimism. I didn’t join Weatherman or anything but I did join Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). I found a chapter at Chapel Hill where I went to school, and so I came up to the edge of where Hannah went and she kept going. And friends of mine did keep going. But it wasn’t hard for me to get back to how angry we were back then in all kinds of ways. And also how strangely optimistic we were at times too, believing that we could actually effect change. Coming out of the Civil Rights movement, partly out of our youth and naivete in many ways, we were optimistic and did believe we could change society, and not just at the edges. But we found out later we couldn’t. But of course at the time, that was not how it seemed. But yeah, I did go back to my own emotional state.

Guernica: In the same interview you said, “So much of the American dream is used to manipulate people into putting themselves at risk and bending themselves all out of shape in order to chase that dream.” Hannah says she’s just hoping, at this point, to break even, to have as many good things as bad things happen in her life. She calls it a “zero-sum game.” Does she rank as one of your more pessimistic, optimistic, or realistic characters?

Russell Banks: (laughs) That’s very late in her game when she says that, too. She realizes she’ll be very lucky if she comes out at zero. She doesn’t speak for me, of course. No character, really—or rarely—speaks for the author. No one wants to end up historically in the same place they started. No one wants to have to repeat history over and over again. That’s too ugly. So you hope and I certainly hope that there’s a kind of evolution going on historically so that we don’t have to repeat everything horrible that has gone on. I wouldn’t say that I’m particularly optimistic about that. But I do know—I’m old enough now to remember a time in the United States when racism was much more dangerous and cruel and pervasive than it is today. It still exists but it was much more overt and structural than today. And I can remember a period in the country when it was much more difficult to be a woman than it is today. My full-grown daughters’ lives are different from their mother’s and certainly very different from their grandmothers’. So there is change. Would I call it progress? I guess we should call it progress.

Guernica: John Kerry makes a little cameo in a letter from Hannah’s parents.

Russell Banks: (laughing) Yeah, that was before the election, too, when I wrote that.

Guernica: Some of the historical figures of Liberia make appearances. Talk to me about these attempts to wedge fictional characters up against historical events and characters that we see both in Cloudsplitter and The Darling.

Russell Banks: Right. Well, there’s several different uses I suppose for historical characters. In the case of John Kerry, that’s almost like a telling detail to identify the class and the sort of social milieu of the parents. He’s useful because he’s associated with Vietnam Veterans Against the War, as we all now know after the election. But in my mind—I knew him actually in the middle 1970s, and I thought he was a very brave man and a very idealistic man at that time. And we know what he became, a sort of middle of the road, ordinary, flatfooted politician. And unctuous and self-righteous. But as a young man he was quite different. So I was just trying to get at that shift in time and so on as well. Then there’s the use of characters like Charles Taylor and Samuel Doe. Once you accept that you’re writing about a historical period and politically identifiable place like Liberia—if I was making up a place like Liberia it would be different, but if I’m really writing about Liberia—then those known historical figures have to be in the story. In some way or other. And in a small country like Liberia, it’s not hard for someone like Hannah, who’s married to someone in government, to get close to those figures. So, it’s plausibility, I suppose, is the other use for historical characters. The same could be said of Cloudsplitter. Along with John Brown are people like Emerson—and they have to appear among the cast, these known figures.

Guernica: Tell me about your process a little, starting with preparation and research. Did you go to Africa, for instance?

Russell Banks: I went to West Africa. I tried to get into Liberia actually, before I finished the book up. I did an awful lot of prep work beforehand, library, reading, talking to people who had spent time there, Peace Corps volunteers, Liberians living in the United States and so on. I even spent an entire weekend with an old CIA hand who’d been stationed in Liberia. So I went over trying to get in, just as I was finishing the book. Really what a novelist goes after is not what a journalist or scholar or historian would. I just wanted to get on the ground and see what it smells like. Or sounds like. You know, taste the food, that sort of thing. And I couldn’t get in because the country had exploded again in violence. And bodies were piling up in the streets of Monrovia, and people were running around firing Kalishnikovs in the air. And the roads were ordered closed, and there was no way to get in. And I thought, well, you know, I’m of an age where I really shouldn’t be doing this, so I stopped at the border. But it turns out I got it well enough right, I think. In fact, last night I was just having dinner and a young man sitting next to me recognized me and had just read the book. He also just got back from ten months in Liberia for an NGO there and was sort of shocked that I hadn’t been there. He’d read it as a road map. It was exact as far as he could see. And then I had Liberians living in the states come to me and say it was a fully accurate picture, and I felt ok about it.

Guernica: Then what’s the process like once you start writing? Do you have a set time when you like to write?

Russell Banks: I work in the mornings. I have a little studio about 200 yards from the house. It’s a renovated old sugar shack once used to water down maple sap into maple syrup, and usually I’m here in the mornings and I work until early afternoon.

Guernica: Tell me a little bit about how you establish a character’s voice?

Russell Banks: Well, the first thing is to establish who the narrator is talking to. Because we all speak differently depending on who we’re talking to. And we leave certain things out and other things in, and we use a different level of diction and our grammar even changes. In Hannah’s case, I decided that she was talking to a man and not a woman. And in my mind it had to be one person, because if you try to speak to more than one person you tend to get vaguer and vaguer. I just imagined she was talking to someone about her age, a man, a white man, a man with some of her experiences and beliefs, but by no means all of them, and it was a neighbor or someone who knew her well—though not a spouse—and so that pretty much described myself (laughs). So I just imagined that I was sitting next to her on her porch the entire summer and she was telling me her story—right here in the town that I live in. Once I had that established in my mind, then it wasn’t difficult to hear her voice, and let her speak. I don’t think of the process as an act of ventriloquism, or speaking through the characters at all. Of course, I’m the one setting the words down on the page. But I’m setting down what I think I hear in my ear.

Guernica: I was fortunate enough to interview your wife once [the poet Chase Twichell] who told me that poetry goes where prose can’t. Do you want to take issue with that?

Russell Banks: (laughs) No, I think she’s right. Having written poetry when I was younger and even occasionally now—the reason being exactly that. It goes to… it’s non-linear, and can be more so than prose. The expectations that we bring to a novel, essay or short story, or even to a sentence, those expectations are very different than what we bring to the line in verse. We simply allow ourselves to be taken somewhere else. It isn’t about language so much as it’s about structure and form and the expectation that the reader brings to it. So, I would agree with her.

Guernica: Good. I wouldn’t want to start anything between--

Russell Banks: No, you wouldn’t start anything.

Guernica: The process of turning your novels into films—has that gone smoothly for you?

Russell Banks: I wouldn’t say altogether smoothly, but it has gone well. I’ve had two adaptations that turned out well, Affliction and The Sweet Hereafter. And I’m working on—when you called I’m sitting here working on about the tenth revision for the script for Continental Drift, which we’re hoping to shoot in February and March of this year coming up. And I’m very happy about it at this point. At the end of the year, I might not be.

Guernica: Do you expect this to lead to another cameo? Is this the end of Russell Banks the writer and beginning of your acting career?

Russell Banks: I don’t think I have the right temperament for an actor. It’s really boring actually. I don’t think I’m very good at it. So I don’t think so.

Guernica: Is there a filmmaker you’d like to work with you haven’t had the chance to yet?

Russell Banks: I’d love to work with Gus van Sant. I admire what he does. Yeah, there’s a lot of filmmakers out there. I’ve been lucky with the ones I have worked with, starting with Atom Egoyan and Paul Schrader and now working with Rauol Peck, a Haitian French director on Continental Drift and Philip Kaufman who directed The Darling—I’ve been very lucky. I think what it is is the people who would be attracted to my books and want to make them movies tend not to be the big studio directors but rather independent-minded and artistically ambitious filmmakers.

Guernica: After this next screenplay, what’s next?

Russell Banks: I’ve been working on a novel most of this year off and on. I can’t say too much about it, but I know it’s set in the year 1936 and set up here in the Adirondacks.

Guernica: It won’t require any attempts to sneak into a war zone?

Russell Banks: No, I don’t think so (laughs). I hope not.