YES, SALLY POTTER

The innovative writer/director discusses her latest film, venturing into uncharted territory, and how A.O. Scott got her movie wrong.

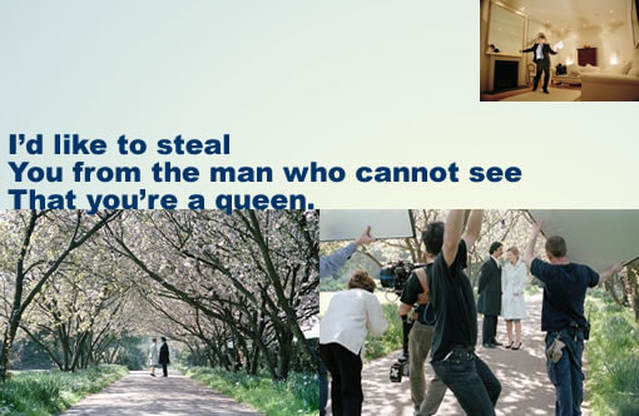

Sally Potter is the writer/director behind such innovative films as The Tango Lesson and Orlando, which was nominated for two Academy Awards. Her latest film Yes, which opened in the U.S. this summer (and opens in Sweden, Norway, Australia and Mexico this fall), features an illicit affair between a couple called simply He (Simon Abkarian) and She (Joan Allen). The context for the film is the world after September 11, and features the struggles of He and She to be intimate as they are assigned and assume roles in that world. The entire film is set to rhymed verse. Writes Kevin Thomas of The Los Angeles Times, “Bold, vibrant and impassioned, YES is the work of a high-risk film artist in command of her medium and gifted in propelling her actors to soaring performances.”

[Interview by Joel Whitney]

Guernica: How did Yes come into being?

Sally Potter: I started writing it on September 12, 2001 as a direct response to the events of the previous day.

Guernica: What made you choose to do the dialogue in iambic pentameter, and—even more astonishing—in rhyme?

Sally Potter: It came out of necessity. The constraint of verse liberated a way of expressing ideas and feelings which are difficult in the different constraint of so-called normal or everyday speech.

Guernica: In most films we see lines of dialogue approximating the thoughts behind them, or even masking thoughts. But Yes seems to get us much more intimate with the characters’ thoughts. You have the things they say delivered in a sort of whispered voiceover soliloquy. Tell me a little about how you came to this technique. Is it drawn from your relationship with the written word?

Sally Potter: More from my relationship with listening, both to the speech of others and to my own thoughts. I tried to listen to soliloquy we each inhabit and find a form for it, a sort of stream. The obvious literary influence, however, is Joyce, as the title is a quote of the last word of Ulysses.

Guernica: One reviewer mentioned Dylan Thomas, Moliere, and, again, James Joyce. And of course there’s Shakespeare. But were any of these in the front of your mind as you made this film?

Sally Potter: Joyce was an inspiration, as I said. But in the front of my mind—and the back and the middle—was to try to find an appropriate form, an explosion of language, that might work cinematically.

Guernica: A.O. Scott, in The New York Times, dismissed Yes as not wanting its audience to think. Any reaction to this?

Sally Potter: A.O. Scott is completely wrong, both in his analysis of the film and in his observations of audience reaction. I have travelled the world with this film and listened to the audiences in countries including Mexico, Germany, Turkey, Cuba, Greece, Japan and in cities across the USA. I have seen people of all ages, both sexes and from many different cultural and ethnic backgrounds weep for and with the characters and also heard them think, reflect and question themselves, the film and their responses. To divide feeling and thought is symptomatic of a resistance to their integration. Some reviewers are in fact finding elaborate ways to describe their own resistance to feeling something which is uncomfortable for them, or to thinking outside their own paradigm. You find clues to this resistance in the tone. The more sneering the tone of the review, the more coded is their own feeling state.

Guernica: Those who’ve championed this film have been adamant in their support. Roger Ebert wrote a second piece in The Sun Times to defend his initial emphatic endorsement of Yes, and to tell Scott he’s wrong. It seems the strong feelings have something to do with the film’s experimental qualities. Were you seeking to be experimental?

Sally Potter: I was trying to be appropriate. Flexible. Open. Adventurous. I was not interested in experiment for its own sake, but I was trying to find ways to express what seems inexpressible, the hidden voices, the secret lives of the protagonists. The language of cinema as it has evolved has also excluded vast swathes of human experience. The forms we find in the process of making a film can start to redress this balance and venture into uncharted territory. This is not just about unsung identities but about the subtleties and nuances of contemplation, the drifting spaces in which the worlds of the very small and the very large collide. Camerawork is a part of that. We called it ‘searching’ for the image.

Guernica: I suppose we should say something about the splendid cast. I read that Joan Allen said this is the closest she’s come to doing Shakespeare. How did this wonderful cast come into place?

Sally Potter: I called them up. We met. We talked. You come to recognise a hunger for work in others, that forms the basis of collaboration. The ensemble. This is the alchemical moment for a director. You place yourself in their hands and they in yours.

Guernica: How did they react to the rhyme? Did you direct them differently? Did you tend to direct them toward highlighting or hiding the rhyme?

Sally Potter: It was all about finding the necessity to speak. Nothing reverent, nothing phoney. Grounding the text in their own experience whilst working with the exterior details too, the ‘mask’ of costume and appearance. We were looking for a kind of transparency in the performances. Something ‘natural’, nothing forced. The rhyme would be there anyway, there was no need to draw attention to it. It was like a hidden pulse, part of the structure of breath. The actors worked boldly and bravely in rehearsal.

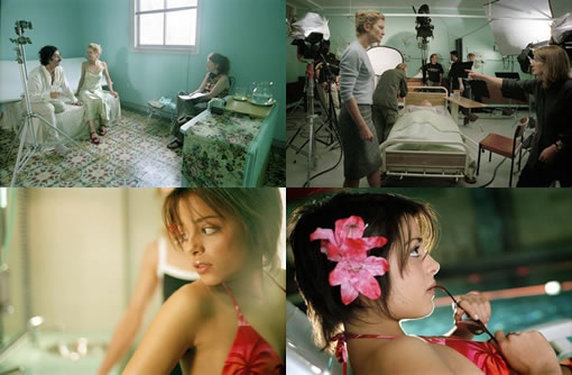

Guernica: The photography was also gorgeous, with the light blues and contrasting colors and the shimmering lights in the pool. How was the film shot?

Sally Potter: The film was shot fast (a 6 week shoot, including travel between the countries). It was shot on super16mm (a 35 mm negative was generated in post-production). The crew was very small and very committed. We worked with what we could find or afford or invent. Carlos Conti (designer) and Alexei Rodionov (DP) were brilliant and generous collaborators.

Guernica: What’s next for you?

Sally Potter: I don’t know. I never know until I start, and I don’t seem to yet have finished with Yes, otherwise I wouldn’t be sitting here discussing this with you!

Sally Potter is the writer/director behind such innovative films as The Tango Lesson and Orlando, which was nominated for two Academy Awards. Her latest film Yes, which opened in the U.S. this summer (and opens in Sweden, Norway, Australia and Mexico this fall), features an illicit affair between a couple called simply He (Simon Abkarian) and She (Joan Allen). The context for the film is the world after September 11, and features the struggles of He and She to be intimate as they are assigned and assume roles in that world. The entire film is set to rhymed verse. Writes Kevin Thomas of The Los Angeles Times, “Bold, vibrant and impassioned, YES is the work of a high-risk film artist in command of her medium and gifted in propelling her actors to soaring performances.”

[Interview by Joel Whitney]

Guernica: How did Yes come into being?

Sally Potter: I started writing it on September 12, 2001 as a direct response to the events of the previous day.

Guernica: What made you choose to do the dialogue in iambic pentameter, and—even more astonishing—in rhyme?

Sally Potter: It came out of necessity. The constraint of verse liberated a way of expressing ideas and feelings which are difficult in the different constraint of so-called normal or everyday speech.

Guernica: In most films we see lines of dialogue approximating the thoughts behind them, or even masking thoughts. But Yes seems to get us much more intimate with the characters’ thoughts. You have the things they say delivered in a sort of whispered voiceover soliloquy. Tell me a little about how you came to this technique. Is it drawn from your relationship with the written word?

Sally Potter: More from my relationship with listening, both to the speech of others and to my own thoughts. I tried to listen to soliloquy we each inhabit and find a form for it, a sort of stream. The obvious literary influence, however, is Joyce, as the title is a quote of the last word of Ulysses.

Guernica: One reviewer mentioned Dylan Thomas, Moliere, and, again, James Joyce. And of course there’s Shakespeare. But were any of these in the front of your mind as you made this film?

Sally Potter: Joyce was an inspiration, as I said. But in the front of my mind—and the back and the middle—was to try to find an appropriate form, an explosion of language, that might work cinematically.

Guernica: A.O. Scott, in The New York Times, dismissed Yes as not wanting its audience to think. Any reaction to this?

Sally Potter: A.O. Scott is completely wrong, both in his analysis of the film and in his observations of audience reaction. I have travelled the world with this film and listened to the audiences in countries including Mexico, Germany, Turkey, Cuba, Greece, Japan and in cities across the USA. I have seen people of all ages, both sexes and from many different cultural and ethnic backgrounds weep for and with the characters and also heard them think, reflect and question themselves, the film and their responses. To divide feeling and thought is symptomatic of a resistance to their integration. Some reviewers are in fact finding elaborate ways to describe their own resistance to feeling something which is uncomfortable for them, or to thinking outside their own paradigm. You find clues to this resistance in the tone. The more sneering the tone of the review, the more coded is their own feeling state.

Guernica: Those who’ve championed this film have been adamant in their support. Roger Ebert wrote a second piece in The Sun Times to defend his initial emphatic endorsement of Yes, and to tell Scott he’s wrong. It seems the strong feelings have something to do with the film’s experimental qualities. Were you seeking to be experimental?

Sally Potter: I was trying to be appropriate. Flexible. Open. Adventurous. I was not interested in experiment for its own sake, but I was trying to find ways to express what seems inexpressible, the hidden voices, the secret lives of the protagonists. The language of cinema as it has evolved has also excluded vast swathes of human experience. The forms we find in the process of making a film can start to redress this balance and venture into uncharted territory. This is not just about unsung identities but about the subtleties and nuances of contemplation, the drifting spaces in which the worlds of the very small and the very large collide. Camerawork is a part of that. We called it ‘searching’ for the image.

Guernica: I suppose we should say something about the splendid cast. I read that Joan Allen said this is the closest she’s come to doing Shakespeare. How did this wonderful cast come into place?

Sally Potter: I called them up. We met. We talked. You come to recognise a hunger for work in others, that forms the basis of collaboration. The ensemble. This is the alchemical moment for a director. You place yourself in their hands and they in yours.

Guernica: How did they react to the rhyme? Did you direct them differently? Did you tend to direct them toward highlighting or hiding the rhyme?

Sally Potter: It was all about finding the necessity to speak. Nothing reverent, nothing phoney. Grounding the text in their own experience whilst working with the exterior details too, the ‘mask’ of costume and appearance. We were looking for a kind of transparency in the performances. Something ‘natural’, nothing forced. The rhyme would be there anyway, there was no need to draw attention to it. It was like a hidden pulse, part of the structure of breath. The actors worked boldly and bravely in rehearsal.

Guernica: The photography was also gorgeous, with the light blues and contrasting colors and the shimmering lights in the pool. How was the film shot?

Sally Potter: The film was shot fast (a 6 week shoot, including travel between the countries). It was shot on super16mm (a 35 mm negative was generated in post-production). The crew was very small and very committed. We worked with what we could find or afford or invent. Carlos Conti (designer) and Alexei Rodionov (DP) were brilliant and generous collaborators.

Guernica: What’s next for you?

Sally Potter: I don’t know. I never know until I start, and I don’t seem to yet have finished with Yes, otherwise I wouldn’t be sitting here discussing this with you!