W.S. MERWIN, FOR A COMING EXTINCTION

The U.S. poet laureate, W.S. Merwin, discusses his role in the antiwar movement, the quagmire of U.S. military occupations, today’s extinction rate, and efforts to conserve nature on Maui.

In July, W.S. Merwin became the first U.S. poet laureate picked during Obama’s incumbency. The Library of Congress, which administers the laureateship, mentioned his translation and environmental work among his accomplishments. Merwin has chosen to emphasize particularly the latter via his efforts to restore rainforest on his Maui property. His translation, arguably, unites the poet with our most multicultural of U.S. presidents, whose ties to Asia (namely, Indonesia) and Africa (Kenya) were for a moment seen as part of a new American multicultural soft power-base. What the Library left totally unmentioned in his laureate’s CV is Merwin’s iconic status as an antiwar figure.

Beginning with 1963’s The Moving Target and 1967’s The Lice, Merwin established himself as one of American poetry’s most versatile figures, uniting visually stunning aesthetics with sixties politics. The politics in his poems, in fact, read like riddles, koans, infused as they are with the poet’s interest in Zen meditation along with translation from across Asia, Europe, and Latin America, without the least loss of clarity. In “The Asians Dying,” Merwin writes of the Vietnam war, “The dead go away like bruises/ The blood vanishes into the poisoned farmlands/ Pain the horizon/ Remains … The possessors move everywhere under Death their star.”

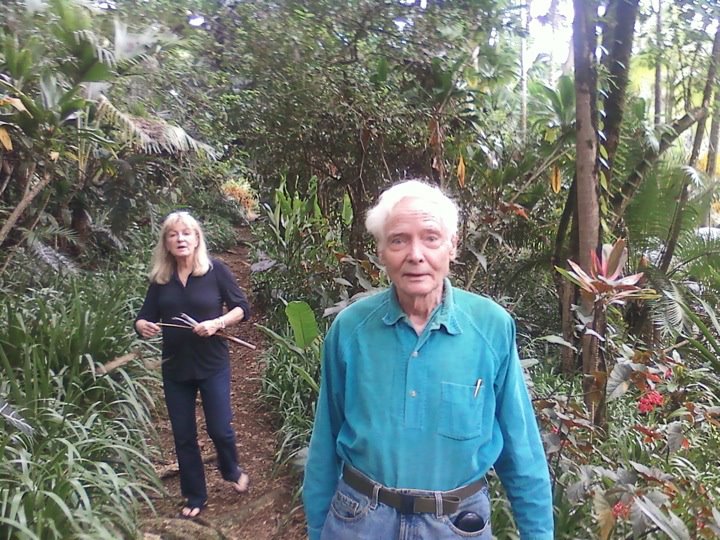

I meet Merwin on a Tuesday in August at his home in Peahi, a valley in the town of Haiku, on the island of Maui. At the time, he is just beginning his stint as poet laureate; today he is halfway through. Merwin and his wife, Paula Schwartz, have invited me for lunch. As we chat their furry chow chow, Peah, barks in the background. We dine on the Merwins’ open-air veranda on a vegetarian pasta while carnivorous mosquitoes feast on us. We are sung to by a Hawaiian thrush perched out on one of the local Pritchardia palm varieties Merwin has planted over three decades of careful forestry. A conscientious pair of hosts, William and Paula are careful to ask questions of their guest, who lives, we discover, near Paula’s son, the novelist John Burnham Schwartz, in Brooklyn.

Born in New York City in 1927, his father a Presbyterian minister, Merwin found from very young that he had a special relationship with words. Recounting one early memory of language, he describes hearing the men painting his family house utter a word he hadn’t heard before, one with special power. “Something went wrong, somebody spilled something. And one of them said, ‘Shit.’ And I said, ‘Shit.’ I was, oh, three and a half. He said, ‘Don’t ever let your father hear you say that.’ And I said, ‘Why not?’ And they said, ‘Nah, nah, you can’t let him hear you say that.’ I couldn’t figure it out. They wouldn’t tell me. And there was a long flight of stairs in the front of the house. And we had a little fox terrier. The fox terrier and I sat on the top step and I had my arm around her and I kept saying, ‘Shit. Shit. Shit, shit.’ And she was sort of interested. [But] she wasn’t shocked. And I thought, What is it about this word?”

Among his most recent collections are The Shadow of Sirius, which won him a second Pulitzer Prize, the riddle-like Present Company, and the massive Migration: New & Selected Poems. When I realize this latter tome starts with a Noah poem, I seize on an unfortunate riff he will tease me about for all its self-consciousness: the engaged poet and environmentalist as Noah. After all, Merwin calls his home state “the extinction capital of the world.” However forced the metaphor, fear of extinction arises repeatedly in our discussion. Otherwise composed, carefree, white-hair gleaming atop his thin frame, with kind, keen eyes, Merwin is singularly agitated by this eventuality. It ranges in our talk from the acceleration of species loss, to clear-cutting in the Northwest United States, to overpopulation in the United Kingdom. In his poetry too.

His signature environmental piece, “For A Coming Extinction” laments: “Gray whale/ Now that we are sending you to The End/ That great god/ Tell him/ That we who follow you invented forgiveness/ And forgive nothing.” In a unique and early American take on surrealism, Merwin found a language particularly to express, as he tells me below, the inexpressible. But it is not merely public, collective; nor could it work if it were. It is deeply personal. “Terrible grief, intense erotic feeling, or even unspeakable anger are all inexpressible,” he says. And it is poetry through which these may be voiced. In fact, states Merwin, “it’s quite possible that language begins with grief.” “Your absence has gone through me,” he writes in the same period, “Like thread through a needle./ Everything I do is stitched with its color.”

—Joel Whitney for Guernica

Joel Whitney: One of the fascinating things about your career is how you unite all these movements—generally great leftist movements: environmentalism, the antiwar movement, the world of American letters, but also literature in translation, an offshoot perhaps of multiculturalism. Most trends, including the president’s “bipartisanship,” pull apart and separate the left. But your work seems to bring it back together.

W.S. Merwin: My generation grew up, or most of us thought we grew up… as freaks, because we grew up into a world where most of the writers and artists and the people who were interested in the arts weren’t interested in the birds and the bees at all. And those who are biologists and botanical and ornithological friends never read a book. We reached the age of maturity, whatever that is, assuming the world was like that. And suddenly you realize it wasn’t so, that there were quite a few contemporaries who felt the same way we did about everything being connected. I don’t think the other point of view makes any sense, except economically. If you want to say “increase” and “multiply” and “have dominion” and you’ve “got a right” to do this and all that, ok. But I think that’s suicide. Whatever you do to the world around you, you’re doing to yourself. I don’t mean that in any particular spiritual so-called way. I mean, actually. I mean if the guys in the Northwest who want to continue cutting down old-growth trees do it, the day will come when there aren’t any old-growth trees to cut down. And then what do they do? They say, Well, they have to do it because of their jobs. Well, there won’t be any jobs because there won’t be any trees to cut.

Joel Whitney: Mark Dowie writes about the advent of nature as a place without people. That’s how separate from it we’ve come to see ourselves; modernity has these little pockets of the primitive, little Eden-islands embedded, called national parks or nature preserves.

W.S. Merwin: There are problems built into the whole situation that are not talked about. I mean, I think there’s something very disturbing [which] doesn’t give much room for optimism for our future in this idea that speed itself is a virtue—just by itself. Because what that means is you become a slave to acceleration. And you buy all of these notions about labor saving and all that, when in fact, I think labor saving doesn’t save labor; it increases expectations. If you’ve got a computer you can turn out more material, so you’re expected to turn out more material. You’re exactly where you were before, but with more demands on you, and everything going faster.

Joel Whitney: You’re reminding me of your poem in Present Company, “To Impatience.”

W.S. Merwin: Well, that’s personal impatience. It’s a little different.

Joel Whitney: You’d think those loggers from the Northwest would—and sometimes I’m sure they do—start to log or think sustainably.

W.S. Merwin: Nobody likes to talk about the issue of population. I think this is part of the whole thing of acceleration. The human species, however you define it, was past the one billion mark, I think it was 1804. Now look where it is; it’s almost seven billion, climbing fast on a sort of sine curve; the farther you go, the faster it goes. And I think that it’s very hard to slow down acceleration. I saw a figure a couple of days ago about the British Isles. It said the British Isles on their own, the ecosystem there, could sustain fifteen million people. Now what are there? Sixty million just in Great Britain? And so where is it coming from, and how’s it going to keep coming—because it did it with the empire and it did it with superior economies exploiting the underdeveloped ones, as they called them. What about when it all gets developed? Of course, another thing that’s accelerating is the extinction of species. In 1980, I think we were losing a species a week. Now I think we’re losing a species every twenty minutes. That’s only in thirty years.

Joel Whitney: Migration is your most recent “selected poems.” I notice the first poem—from your first book, and it’s the only poem from that book—is a Noah poem. I thought, there’s an echo with what you seem to be doing here in Haiku. I understand you’re planting endangered palms from around the world.

W.S. Merwin: I never thought of that. It’s a poem that I realized after I’d written it that I’d been trying to write for a couple of years. And I seemed to have ruined it several times. I would go back to it months later after I’d sort of forgotten it. All of a sudden it happened.

Joel Whitney: I know that your dad was a Presbyterian minister. Was the Noah and the ark story something that impressed you as a boy?

W.S. Merwin: I loved that story so much. And I had this fantasy of building an ark in the back yard, because when the rains came, I said, you know, nobody believed Noah. Nobody will believe us either. We can build this boat, but [smirking] where are we going to get the animals?

Joel Whitney: I imagine you have many here.

W.S. Merwin: Not as many as you think. You know Hawaii is the extinction capital of the world in some ways. Of all the native birds that were here when Cook arrived, well over half are extinct now and over half the remainder are on the endangered species list. It’s just terrible. The English brought in malaria. A captain brought it in deliberately. I mean, not malaria, mosquitoes. And the mosquitoes brought the malaria. And the malaria included avian malaria, and just within a very short time wiped out all the native birds up to four thousand feet. Now the mosquitoes are getting acclimated to move up the mountain. Several species have become extinct just between here and Hana, just in the past five years.

Joel Whitney: It seems there’s a terrific connection with Asia in your work. And I notice around The Moving Target (1963) is when the punctuation leaves your work. Is any of that coming from the Asian translations that wound up in East Window?

W.S. Merwin: Most of that work was done ten years or so later.

Joel Whitney: I know you’ve written that you felt that punctuation was nailing the poems to the page, and you wanted to lift the poems off the page. But it seems like such a clever way to get the reader to become active in reading the poems, almost choosing for herself where to pause or stop—where to punctuate. Is that my imposing a purpose or is that part of it?

W.S. Merwin: It was that partly. And I thought, you know, poetry for a long time, a great deal of poetry was never punctuated. Medieval poetry was very often not punctuated at all. And then I read some Apollinaire whom I loved very much—I saw by reading him that anything you do as a condition of a poem becomes a form by itself. If you stop using punctuation, that’s a kind of formality. I mean you have to be very conscious of the grammar and the syntax and how the sentence is put together; otherwise it’ll be just so ambiguous and confusing you just won’t be able to read it. The other thing I think it does is to make the separation between poetry and prose. I thought, punctuation is very convenient, but it was really invented in the seventeenth century for prose. Not for poetry at all. The punctuation of Shakespeare texts is whatever seemed convenient. There weren’t any particular rules that he was following that I can see. I mean it changed in the course of the plays. But above all, I thought that having no punctuation made you listen to the poem. That’s the important thing. I think if you don’t listen to poetry… everybody who reads poetry understands this without talking about it. But people who don’t read poetry don’t listen to it. They read it the way you read an article in the Times or something like that, basically for information. And poetry’s not there for information.

Joel Whitney: Maybe just to complicate that, since you’re now our public poet in the U.S.: The Moving Target and then The Lice have some of those great antiwar poems like “The Asians Dying”—they do have those great sounds in them, those drops that drop again and again in the eyes of the dead. And great images, like the time of separation, in “When You Go Away” being “the time when the beards of the dead get their growth.” And what you just said about hearing them—I think the punctuation has all but gone away then. Poetry is about sound, which is there, but not about information. Yet there is information in those poems. There is a content. Were you working outside of poetry on any sort of antiwar campaigns, and how did that become content for your poems?

W.S. Merwin: Yes. But I was… Bly and I used to have arguments about that. Well, not arguments. Differences. Because I said, You know, Robert, it’s pointless to keep repeating yourself. You want to make a statement, if necessary, when the time comes. But if you repeat yourself too much you become predictable, and they know what to expect and they just write you off as someone who has that opinion.

Joel Whitney: And so you won’t be heard at all, listened to.

W.S. Merwin: You won’t be heard. It’s much more important to think about it, to be very clear about it, so that if someone confronts you or asks you a question or something, you can come out right there and say exactly how you think about it, and why. And that will have a freshness that will be much more powerful than coming out with the old drumbeat again.

Joel Whitney: Essentially, as poet laureate, you’re President Obama’s poet laureate, is that right?

W.S. Merwin: I think that’s part of the idea.

Joel Whitney: So what about this war? What about the Wikileaks cache of documents, the apparent war crimes we see in the “Collateral Murder” video?

W.S. Merwin: I feel very bad about this war. I have since the beginning. I realize [the president] had such potential enemies from the beginning and he didn’t want to alienate the military too. I can see probably why he got into it. But I think it’s hopeless. I think our presence on the ground from the Mediterranean to Afghanistan is a morass. It’s quicksand that we’ll never get out of. And whatever we may seem to achieve will last a very short time after we’ve left. This is a great ancient tradition. It’s not a happy one. And it’s not altogether constructive; it’s also been very violent and very cruel, just as we have. But we’re not [all] the same. And also the idea of democracy, which I think is a fragile, magnificent achievement. But we can’t expect everyone else to just turn around and say, What a great idea.

Joel Whitney: Have you followed the documents released in the Wikileaks cache? Going through the documents you see the problem of civilian casualties is just amazing and awful. But it sounds like you see some of Obama’s actions as a concession to an intractable military establishment. (Which is scary.)

W.S. Merwin: I think so. And I don’t in anything I say mean to dishonor people who think they are doing the right thing and are risking their lives to do it. Your [great-grandmother] was a Quaker. Well, my mother was too. She wasn’t a card-carrying Quaker but she was extremely interested in Quakers.

Paula Schwartz: Your mother was a real pacifist.

W.S. Merwin: Yeah, she was.

Paula Schwartz: But you consider yourself not a pacifist…

W.S. Merwin: I never use the word [pacifist] any more than I use the word vegetarian. Because I can imagine circumstances in which violence is the only answer and they’re extremely unpleasant circumstances.

Joel Whitney: Would that be self-defense?

W.S. Merwin: Self-defense or somebody beating a child or an animal or deliberate cruelty which can’t be stopped in some other way. You’re either ashamed of yourself for being so inadequate that you don’t do anything or you stop it by whatever means possible. And that probably means violence in those circumstances. And I don’t have any illusions about that either. Because I think violence, however good the motive, leads to more violence and to destruction and… But the thing that has upset me since the age of eighteen when I was a conscientious objector—I wouldn’t call it that because I didn’t believe that anyone had the right to ask me whether I believed in a supreme being; I thought that’s nobody’s business… But [since then] I felt organized violence in which one promises to obey someone whom one may not even know (and for whom one may have no respect) for reasons that one doesn’t know very much about, at the orders of higher-ups about whom one knows nothing (and that involve the lives of other people whom one doesn’t know)—this doesn’t make any sense to me.

Joel Whitney: When you published “The Asians Dying,” “The Students of Justice,” “The Moving Target,” “When the War is Over,” some of them were great antiwar poems. Some of them seemed calls to environmental consciousness. Did you perceive a recognizable impact from those?

W.S. Merwin: Some of them were used and reproduced and circulated. There was the whale poem, “For a Coming Extinction;” there were several broadsides made about that one, especially on the West Coast. But all the time, you know the whole thing that happened certainly since the nineteenth century and probably before that, there are assumptions about poetry: poetry doesn’t get involved with politics, poetry doesn’t get involved with any of these things, it’s sort of above all that. You don’t take positions, you don’t do any of that. But I couldn’t ever just acquiesce on that and be happy about it. I didn’t think that writing political poetry is a great thing to do. But I don’t think writing love poetry is a great thing to do. There’s an awful lot of both kinds of poetry. You know, you write it.

Joel Whitney: It happens.

W.S. Merwin: There were two things that kept at me about that. One of them was Albert Camus, saying those of us who speak have a responsibility to speak for those who can’t. (And the other person who will tell you the same thing, and we’ve agreed about it all our lives, is Peter Matthiessen. We’ve talked about Camus and we’ve talked about that passage.) And the other guide for me, the other reminder, and stern teacher in some ways was Dante. Dante is not so pure that… He tries to bring the whole history of his time into the [work]. I don’t believe this is something that you can do as an act of will but you can try to do it, and probably fail quite a lot of times. And I think that anger is one of the most dangerous and difficult subjects in poetry. And political poetry has got two strikes against it. Because it starts by knowing too much and you’re having an opinion and wanting to persuade somebody else of your opinion. But Shakespeare’s not trying to persuade anybody of anything with the sonnets, you know. And most of the poetry that we love isn’t.

Joel Whitney: He might be trying to persuade a reader how powerful his love is in some of the sonnets.

W.S. Merwin: Oh sure. That’s a different matter. That’s why… Was it Rexroth who said—they asked him why he wrote poems and he said, “I write poetry to seduce women and to overthrow the capitalist system… In that order.” Rexroth tried to incorporate supposedly unpoetic material into his poems, some of the long poems. Very often it was a not very interesting effect. But he did try.

Joel Whitney: I know what an effect translating had on you, and I know Lorca and Pablo Neruda, to name two, had a huge influence. How different a poet do you think you’d be if you had only read work in English?

W.S. Merwin: I can’t tell, but I think much more limited. Poetry, like the imagination itself, must be limitless. And there must be other ways of expressing the inexpressible, which is what—poetry is just that. Prose is about what can be said and what is known and so on. Poetry is about what cannot be expressed. I mean, terrible grief, or intense erotic feeling, or even unspeakable anger are all inexpressible. You can’t put them in words and that’s why you try to put them in words. Because that’s all you’ve got. That’s another reason why I think that poetry is as ancient as language itself, because I think language must come out of an urge for which there was no expression, no way of doing it. I mean grief or fear or rage or whatever it was. It goes from one roar or one scream or one terrible sound of pain to starting to articulate it. It’s the articulating that becomes poetry. But it doesn’t become information at that point. It’s closer to translation. It’s translating something that’s there, that is only to a degree expressible.

Joel Whitney: So translating really helps because it helps illuminate that relationship?

W.S. Merwin: Yeah. Translating is about articulation. It’s not just about carrying something over. I mean, after all, if you translate poetry, which as we know can’t be done… but, you know as much as you can, about what a passage or a line or any part of the poem means, what its prose meaning, what its denotation is, all of that, and don’t dismiss it—this is the way I feel about it. And that’s not what makes it work in English either. And you go on and realize that, yeah, there’s another way of saying that, and then you think, well, there’s still another way of saying that, until you get a way of saying which seems closer to being a poem and closer to… just as close and probably closer to the full meaning of the original. I think of translation that way. After all, translation is a confusing word, because it’s come to mean everything from prose trot to something that takes vast liberties with the original. The translations, so-called, of the sixties were pretty free and easy. You wouldn’t recognize the original. Clarence Brown said to me about someone who did a translation of [Osip] Mandelstam: “Well, nobody would recognize that as Mandelstam except by dental impression.”

Joel Whitney: You mention rage, grief, erotic passion as inexpressible emotions behind the poetic impulse. Or behind the primal urge to express. It seems of those three, grief—perhaps over loss or absence—is the one you have been most concerned with.

W.S. Merwin: I think it’s quite possible that language begins with grief. You know, you see the Iraqi woman whose husband has just been killed by a bomb in front of her and that open mouth. That’s the origin of language right there. Grief and joy are never far apart.

Joel Whitney: Octavio Paz wrote of the first people coming out of a cave and looking up at the stars and just being filled with awe and joy—and he said there’s where poetry came from.

W.S. Merwin: Yeah, because joy, too, is inexpressible. When you come to that moment, what can you say? You just look.

Joel Whitney: Let’s talk about some of the writers you did translate. Did you meet Borges?

W.S. Merwin: I did. I introduced him one night at the 92nd Street Y [in New York] many years ago. Very young. And there’s a picture. I think it was Jill Krementz took it, and she showed it to me many years later. And she said there’s a picture of me sitting on the arm of the easy chair in the green room. And in the easy chair is Borges, looking up. And we’re having an obviously very close conversation. She said, Do you remember this? I said, I not only remember it, I remember the evening very well and I remember what we were talking about. She said, What was that? And I said, He had just recited by heart, in English, Milton’s sonnet, “On His Blindness,” and we were talking about that poem. And how he loved it. And, you know, Milton wrote that poem as quite a young man and there’s a lot of piety… the Puritanical piety that runs through Milton’s poems. But it doesn’t wreck the poem, because he’s talking about being guided by this passion, which in his case, he doesn’t separate his religious belief from his poetry. He never did. Although I think the more secular poems of Milton are some of his most beautiful. One of the greats is “On His Deceased Wife,” remember? Where he says, “Methought I saw my late espousèd Saint/ Brought to me like Alcestis from the grave.” And so different from the sonnets of Shakespeare.

Joel Whitney: So that was the thrust of your conversation with Borges. Did you stay in touch with him?

W.S. Merwin: Not really. I don’t think he wrote letters very much by then; he dictated letters. And when he gave talks, he did them more or less from memory. He ad-libbed them and he made them up to some degree. Was it Seven Nights, that book of talks that he composed and delivered after he lost his sight, when he couldn’t read off the platform anymore? But you know he lost a lot of his sight quite early.

Joel Whitney: It seemed to come in stages.

W.S. Merwin: It was genetic. I mean he had had parents and grandparents, all of whom had lost theirs.

Joel Whitney: His dad had lost much of his sight.

W.S. Merwin: Was it his dad? I thought it was his mother’s side too.

Joel Whitney: His dad took the family to Europe in part because he needed eye surgery. There’s a [relatively] new biography by Edwin Williamson.

W.S. Merwin: I haven’t read that one.

Joel Whitney: But you clearly love literary biography, and encounters. Wasn’t there another Borges encounter that had to do with Robert Graves?

W.S. Merwin: Yes, with Alastair Reid. Alastair succeeded me in the job with Robert Graves [as his assistant], and then he and Robert had a falling out. Robert did with everybody. Alastair tried to stay friends with Robert and he did stay friends with Beryl [Robert’s wife], and would go out and visit her. He had a house of his own on Mallorca and his son lived on Mallorca, too. So he was in Mallorca quite a lot in those days, the last years of Graves’s life. And in Palma there was one cafe that we all used to go to, Figaro. When we finished our shopping we would go and drink at Figaro. Alastair went and he was having a drink and he looked and a few tables away, there was Borges and [his wife] Maria Kodama. And he went over and spoke to Borges and said, “What are you doing here?” And Borges said, “Oh, I’m on a pilgrimage” [Merwin imitates the Argentine accent, laughing]. And Alastair said, “Yes, what kind?” And he said, “I’m going to see don Roberto Graves.” So Alastair thought, Oh my god. Because this was in the early eighties. Robert had, as Alastair said, lost his marbles. And he was really gone. And he was a really big man and he kept falling out of bed, and so they had to put him in an oversized crib, with a thing [bars] around it.

And Alastair thought, This is going to be a disaster, him going out to see Robert. And he said, “Would you like me to come with you?” And Borges said, “Oh yes, I’d love that.” So in those days you still took the little train from Palma out to Soller and then took a car up to Deià . They did, and they went to see Beryl and Beryl let them in and she was a little bit anxious too. You know, Robert didn’t like other writers… I’m sure he never read any Borges. And he didn’t know who it was anyway. I mean, he was just lying in bed, gaga. And Borges tried to make conversation and was talking to Robert and was getting nothing back but the occasional sort of monosyllabic nothing. And Alastair finally said to Borges, “I think that don Roberto is probably a little bit tired.” And he took Robert’s hand and brought it out through the bars of the crib. And he took Borges’s hand and put it in Robert’s hand, and there they were for some minutes, holding hands. In totally different worlds. Completely unaware. And that made a good moment for farewell and he could say Borges could make his rather courtly farewell to Robert, which was unacknowledged, and off they went. It’s totally grotesque to think about, one totally blind and unaware, and the other completely gaga and unaware.

Joel Whitney: That’s sort of remarkable. Tell me more about your translating work. The East Window: Poems from Asia offers that terrific series of “figures”—those haikulike, proverb-like epigrams from Korea and the Philippines and elsewhere. And you translated so much from South America, including Borges, and from Europe. To account for this much, you’ve made it clear you worked with co-translators to cover languages you don’t speak.

W.S. Merwin: One of the (I think) good but dangerous ideas that came out and was acted upon in the sixties was that it was not necessary to know the language. You could work with someone else. The other idea that was even more dangerous was that you could write your own poem on the material that was there in the original poem. Which is something that should have been explored but not clung to as a right to do that. Because it’s a little misleading and shouldn’t be called translation. It should be called a version or adaption or something quite different that makes it clear that you don’t trust this as a translation. Because translation is a precious thing on its own and not everything is a translation. I mean, the pony is not a translation either. I think one of the ideas is that you could work with somebody else. When I was asked to do a Mandelstam obviously they must have known I didn’t know any Russian. And I said I would only conceive of working on Mandelstam with Clarence Brown.

Clarence was the guy who got Mandelstam’s texts out of Russia. They had never been published. He died in a prison camp. They got rid of him. And his wife memorized all of the Mandelstam and for thirty years recited it to keep it going. And when she began getting older, she recited all those poems to Clarence, who wrote them down on her kitchen table and smuggled it out of Russia. That became the New York edition of Mandelstam. I said I would only do it if I could do it with Clarence. And he said he would only do it with me if I would promise not to try to learn Russian. He said it would just confuse things. But every translation is limited. Clarence said wonderful things in the course of that work. I was depressed about one of them one day, and Clarence said, “Don’t worry. No translation ever ruined the original.”

Joel Whitney: Now, what are you planting here and what are the long-term plans for the Merwin Conservancy?

In July, W.S. Merwin became the first U.S. poet laureate picked during Obama’s incumbency. The Library of Congress, which administers the laureateship, mentioned his translation and environmental work among his accomplishments. Merwin has chosen to emphasize particularly the latter via his efforts to restore rainforest on his Maui property. His translation, arguably, unites the poet with our most multicultural of U.S. presidents, whose ties to Asia (namely, Indonesia) and Africa (Kenya) were for a moment seen as part of a new American multicultural soft power-base. What the Library left totally unmentioned in his laureate’s CV is Merwin’s iconic status as an antiwar figure.

Beginning with 1963’s The Moving Target and 1967’s The Lice, Merwin established himself as one of American poetry’s most versatile figures, uniting visually stunning aesthetics with sixties politics. The politics in his poems, in fact, read like riddles, koans, infused as they are with the poet’s interest in Zen meditation along with translation from across Asia, Europe, and Latin America, without the least loss of clarity. In “The Asians Dying,” Merwin writes of the Vietnam war, “The dead go away like bruises/ The blood vanishes into the poisoned farmlands/ Pain the horizon/ Remains … The possessors move everywhere under Death their star.”

I meet Merwin on a Tuesday in August at his home in Peahi, a valley in the town of Haiku, on the island of Maui. At the time, he is just beginning his stint as poet laureate; today he is halfway through. Merwin and his wife, Paula Schwartz, have invited me for lunch. As we chat their furry chow chow, Peah, barks in the background. We dine on the Merwins’ open-air veranda on a vegetarian pasta while carnivorous mosquitoes feast on us. We are sung to by a Hawaiian thrush perched out on one of the local Pritchardia palm varieties Merwin has planted over three decades of careful forestry. A conscientious pair of hosts, William and Paula are careful to ask questions of their guest, who lives, we discover, near Paula’s son, the novelist John Burnham Schwartz, in Brooklyn.

Born in New York City in 1927, his father a Presbyterian minister, Merwin found from very young that he had a special relationship with words. Recounting one early memory of language, he describes hearing the men painting his family house utter a word he hadn’t heard before, one with special power. “Something went wrong, somebody spilled something. And one of them said, ‘Shit.’ And I said, ‘Shit.’ I was, oh, three and a half. He said, ‘Don’t ever let your father hear you say that.’ And I said, ‘Why not?’ And they said, ‘Nah, nah, you can’t let him hear you say that.’ I couldn’t figure it out. They wouldn’t tell me. And there was a long flight of stairs in the front of the house. And we had a little fox terrier. The fox terrier and I sat on the top step and I had my arm around her and I kept saying, ‘Shit. Shit. Shit, shit.’ And she was sort of interested. [But] she wasn’t shocked. And I thought, What is it about this word?”

Among his most recent collections are The Shadow of Sirius, which won him a second Pulitzer Prize, the riddle-like Present Company, and the massive Migration: New & Selected Poems. When I realize this latter tome starts with a Noah poem, I seize on an unfortunate riff he will tease me about for all its self-consciousness: the engaged poet and environmentalist as Noah. After all, Merwin calls his home state “the extinction capital of the world.” However forced the metaphor, fear of extinction arises repeatedly in our discussion. Otherwise composed, carefree, white-hair gleaming atop his thin frame, with kind, keen eyes, Merwin is singularly agitated by this eventuality. It ranges in our talk from the acceleration of species loss, to clear-cutting in the Northwest United States, to overpopulation in the United Kingdom. In his poetry too.

His signature environmental piece, “For A Coming Extinction” laments: “Gray whale/ Now that we are sending you to The End/ That great god/ Tell him/ That we who follow you invented forgiveness/ And forgive nothing.” In a unique and early American take on surrealism, Merwin found a language particularly to express, as he tells me below, the inexpressible. But it is not merely public, collective; nor could it work if it were. It is deeply personal. “Terrible grief, intense erotic feeling, or even unspeakable anger are all inexpressible,” he says. And it is poetry through which these may be voiced. In fact, states Merwin, “it’s quite possible that language begins with grief.” “Your absence has gone through me,” he writes in the same period, “Like thread through a needle./ Everything I do is stitched with its color.”

—Joel Whitney for Guernica

Joel Whitney: One of the fascinating things about your career is how you unite all these movements—generally great leftist movements: environmentalism, the antiwar movement, the world of American letters, but also literature in translation, an offshoot perhaps of multiculturalism. Most trends, including the president’s “bipartisanship,” pull apart and separate the left. But your work seems to bring it back together.

W.S. Merwin: My generation grew up, or most of us thought we grew up… as freaks, because we grew up into a world where most of the writers and artists and the people who were interested in the arts weren’t interested in the birds and the bees at all. And those who are biologists and botanical and ornithological friends never read a book. We reached the age of maturity, whatever that is, assuming the world was like that. And suddenly you realize it wasn’t so, that there were quite a few contemporaries who felt the same way we did about everything being connected. I don’t think the other point of view makes any sense, except economically. If you want to say “increase” and “multiply” and “have dominion” and you’ve “got a right” to do this and all that, ok. But I think that’s suicide. Whatever you do to the world around you, you’re doing to yourself. I don’t mean that in any particular spiritual so-called way. I mean, actually. I mean if the guys in the Northwest who want to continue cutting down old-growth trees do it, the day will come when there aren’t any old-growth trees to cut down. And then what do they do? They say, Well, they have to do it because of their jobs. Well, there won’t be any jobs because there won’t be any trees to cut.

Joel Whitney: Mark Dowie writes about the advent of nature as a place without people. That’s how separate from it we’ve come to see ourselves; modernity has these little pockets of the primitive, little Eden-islands embedded, called national parks or nature preserves.

W.S. Merwin: There are problems built into the whole situation that are not talked about. I mean, I think there’s something very disturbing [which] doesn’t give much room for optimism for our future in this idea that speed itself is a virtue—just by itself. Because what that means is you become a slave to acceleration. And you buy all of these notions about labor saving and all that, when in fact, I think labor saving doesn’t save labor; it increases expectations. If you’ve got a computer you can turn out more material, so you’re expected to turn out more material. You’re exactly where you were before, but with more demands on you, and everything going faster.

Joel Whitney: You’re reminding me of your poem in Present Company, “To Impatience.”

W.S. Merwin: Well, that’s personal impatience. It’s a little different.

Joel Whitney: You’d think those loggers from the Northwest would—and sometimes I’m sure they do—start to log or think sustainably.

W.S. Merwin: Nobody likes to talk about the issue of population. I think this is part of the whole thing of acceleration. The human species, however you define it, was past the one billion mark, I think it was 1804. Now look where it is; it’s almost seven billion, climbing fast on a sort of sine curve; the farther you go, the faster it goes. And I think that it’s very hard to slow down acceleration. I saw a figure a couple of days ago about the British Isles. It said the British Isles on their own, the ecosystem there, could sustain fifteen million people. Now what are there? Sixty million just in Great Britain? And so where is it coming from, and how’s it going to keep coming—because it did it with the empire and it did it with superior economies exploiting the underdeveloped ones, as they called them. What about when it all gets developed? Of course, another thing that’s accelerating is the extinction of species. In 1980, I think we were losing a species a week. Now I think we’re losing a species every twenty minutes. That’s only in thirty years.

Joel Whitney: Migration is your most recent “selected poems.” I notice the first poem—from your first book, and it’s the only poem from that book—is a Noah poem. I thought, there’s an echo with what you seem to be doing here in Haiku. I understand you’re planting endangered palms from around the world.

W.S. Merwin: I never thought of that. It’s a poem that I realized after I’d written it that I’d been trying to write for a couple of years. And I seemed to have ruined it several times. I would go back to it months later after I’d sort of forgotten it. All of a sudden it happened.

Joel Whitney: I know that your dad was a Presbyterian minister. Was the Noah and the ark story something that impressed you as a boy?

W.S. Merwin: I loved that story so much. And I had this fantasy of building an ark in the back yard, because when the rains came, I said, you know, nobody believed Noah. Nobody will believe us either. We can build this boat, but [smirking] where are we going to get the animals?

Joel Whitney: I imagine you have many here.

W.S. Merwin: Not as many as you think. You know Hawaii is the extinction capital of the world in some ways. Of all the native birds that were here when Cook arrived, well over half are extinct now and over half the remainder are on the endangered species list. It’s just terrible. The English brought in malaria. A captain brought it in deliberately. I mean, not malaria, mosquitoes. And the mosquitoes brought the malaria. And the malaria included avian malaria, and just within a very short time wiped out all the native birds up to four thousand feet. Now the mosquitoes are getting acclimated to move up the mountain. Several species have become extinct just between here and Hana, just in the past five years.

Joel Whitney: It seems there’s a terrific connection with Asia in your work. And I notice around The Moving Target (1963) is when the punctuation leaves your work. Is any of that coming from the Asian translations that wound up in East Window?

W.S. Merwin: Most of that work was done ten years or so later.

Joel Whitney: I know you’ve written that you felt that punctuation was nailing the poems to the page, and you wanted to lift the poems off the page. But it seems like such a clever way to get the reader to become active in reading the poems, almost choosing for herself where to pause or stop—where to punctuate. Is that my imposing a purpose or is that part of it?

W.S. Merwin: It was that partly. And I thought, you know, poetry for a long time, a great deal of poetry was never punctuated. Medieval poetry was very often not punctuated at all. And then I read some Apollinaire whom I loved very much—I saw by reading him that anything you do as a condition of a poem becomes a form by itself. If you stop using punctuation, that’s a kind of formality. I mean you have to be very conscious of the grammar and the syntax and how the sentence is put together; otherwise it’ll be just so ambiguous and confusing you just won’t be able to read it. The other thing I think it does is to make the separation between poetry and prose. I thought, punctuation is very convenient, but it was really invented in the seventeenth century for prose. Not for poetry at all. The punctuation of Shakespeare texts is whatever seemed convenient. There weren’t any particular rules that he was following that I can see. I mean it changed in the course of the plays. But above all, I thought that having no punctuation made you listen to the poem. That’s the important thing. I think if you don’t listen to poetry… everybody who reads poetry understands this without talking about it. But people who don’t read poetry don’t listen to it. They read it the way you read an article in the Times or something like that, basically for information. And poetry’s not there for information.

Joel Whitney: Maybe just to complicate that, since you’re now our public poet in the U.S.: The Moving Target and then The Lice have some of those great antiwar poems like “The Asians Dying”—they do have those great sounds in them, those drops that drop again and again in the eyes of the dead. And great images, like the time of separation, in “When You Go Away” being “the time when the beards of the dead get their growth.” And what you just said about hearing them—I think the punctuation has all but gone away then. Poetry is about sound, which is there, but not about information. Yet there is information in those poems. There is a content. Were you working outside of poetry on any sort of antiwar campaigns, and how did that become content for your poems?

W.S. Merwin: Yes. But I was… Bly and I used to have arguments about that. Well, not arguments. Differences. Because I said, You know, Robert, it’s pointless to keep repeating yourself. You want to make a statement, if necessary, when the time comes. But if you repeat yourself too much you become predictable, and they know what to expect and they just write you off as someone who has that opinion.

Joel Whitney: And so you won’t be heard at all, listened to.

W.S. Merwin: You won’t be heard. It’s much more important to think about it, to be very clear about it, so that if someone confronts you or asks you a question or something, you can come out right there and say exactly how you think about it, and why. And that will have a freshness that will be much more powerful than coming out with the old drumbeat again.

Joel Whitney: Essentially, as poet laureate, you’re President Obama’s poet laureate, is that right?

W.S. Merwin: I think that’s part of the idea.

Joel Whitney: So what about this war? What about the Wikileaks cache of documents, the apparent war crimes we see in the “Collateral Murder” video?

W.S. Merwin: I feel very bad about this war. I have since the beginning. I realize [the president] had such potential enemies from the beginning and he didn’t want to alienate the military too. I can see probably why he got into it. But I think it’s hopeless. I think our presence on the ground from the Mediterranean to Afghanistan is a morass. It’s quicksand that we’ll never get out of. And whatever we may seem to achieve will last a very short time after we’ve left. This is a great ancient tradition. It’s not a happy one. And it’s not altogether constructive; it’s also been very violent and very cruel, just as we have. But we’re not [all] the same. And also the idea of democracy, which I think is a fragile, magnificent achievement. But we can’t expect everyone else to just turn around and say, What a great idea.

Joel Whitney: Have you followed the documents released in the Wikileaks cache? Going through the documents you see the problem of civilian casualties is just amazing and awful. But it sounds like you see some of Obama’s actions as a concession to an intractable military establishment. (Which is scary.)

W.S. Merwin: I think so. And I don’t in anything I say mean to dishonor people who think they are doing the right thing and are risking their lives to do it. Your [great-grandmother] was a Quaker. Well, my mother was too. She wasn’t a card-carrying Quaker but she was extremely interested in Quakers.

Paula Schwartz: Your mother was a real pacifist.

W.S. Merwin: Yeah, she was.

Paula Schwartz: But you consider yourself not a pacifist…

W.S. Merwin: I never use the word [pacifist] any more than I use the word vegetarian. Because I can imagine circumstances in which violence is the only answer and they’re extremely unpleasant circumstances.

Joel Whitney: Would that be self-defense?

W.S. Merwin: Self-defense or somebody beating a child or an animal or deliberate cruelty which can’t be stopped in some other way. You’re either ashamed of yourself for being so inadequate that you don’t do anything or you stop it by whatever means possible. And that probably means violence in those circumstances. And I don’t have any illusions about that either. Because I think violence, however good the motive, leads to more violence and to destruction and… But the thing that has upset me since the age of eighteen when I was a conscientious objector—I wouldn’t call it that because I didn’t believe that anyone had the right to ask me whether I believed in a supreme being; I thought that’s nobody’s business… But [since then] I felt organized violence in which one promises to obey someone whom one may not even know (and for whom one may have no respect) for reasons that one doesn’t know very much about, at the orders of higher-ups about whom one knows nothing (and that involve the lives of other people whom one doesn’t know)—this doesn’t make any sense to me.

Joel Whitney: When you published “The Asians Dying,” “The Students of Justice,” “The Moving Target,” “When the War is Over,” some of them were great antiwar poems. Some of them seemed calls to environmental consciousness. Did you perceive a recognizable impact from those?

W.S. Merwin: Some of them were used and reproduced and circulated. There was the whale poem, “For a Coming Extinction;” there were several broadsides made about that one, especially on the West Coast. But all the time, you know the whole thing that happened certainly since the nineteenth century and probably before that, there are assumptions about poetry: poetry doesn’t get involved with politics, poetry doesn’t get involved with any of these things, it’s sort of above all that. You don’t take positions, you don’t do any of that. But I couldn’t ever just acquiesce on that and be happy about it. I didn’t think that writing political poetry is a great thing to do. But I don’t think writing love poetry is a great thing to do. There’s an awful lot of both kinds of poetry. You know, you write it.

Joel Whitney: It happens.

W.S. Merwin: There were two things that kept at me about that. One of them was Albert Camus, saying those of us who speak have a responsibility to speak for those who can’t. (And the other person who will tell you the same thing, and we’ve agreed about it all our lives, is Peter Matthiessen. We’ve talked about Camus and we’ve talked about that passage.) And the other guide for me, the other reminder, and stern teacher in some ways was Dante. Dante is not so pure that… He tries to bring the whole history of his time into the [work]. I don’t believe this is something that you can do as an act of will but you can try to do it, and probably fail quite a lot of times. And I think that anger is one of the most dangerous and difficult subjects in poetry. And political poetry has got two strikes against it. Because it starts by knowing too much and you’re having an opinion and wanting to persuade somebody else of your opinion. But Shakespeare’s not trying to persuade anybody of anything with the sonnets, you know. And most of the poetry that we love isn’t.

Joel Whitney: He might be trying to persuade a reader how powerful his love is in some of the sonnets.

W.S. Merwin: Oh sure. That’s a different matter. That’s why… Was it Rexroth who said—they asked him why he wrote poems and he said, “I write poetry to seduce women and to overthrow the capitalist system… In that order.” Rexroth tried to incorporate supposedly unpoetic material into his poems, some of the long poems. Very often it was a not very interesting effect. But he did try.

Joel Whitney: I know what an effect translating had on you, and I know Lorca and Pablo Neruda, to name two, had a huge influence. How different a poet do you think you’d be if you had only read work in English?

W.S. Merwin: I can’t tell, but I think much more limited. Poetry, like the imagination itself, must be limitless. And there must be other ways of expressing the inexpressible, which is what—poetry is just that. Prose is about what can be said and what is known and so on. Poetry is about what cannot be expressed. I mean, terrible grief, or intense erotic feeling, or even unspeakable anger are all inexpressible. You can’t put them in words and that’s why you try to put them in words. Because that’s all you’ve got. That’s another reason why I think that poetry is as ancient as language itself, because I think language must come out of an urge for which there was no expression, no way of doing it. I mean grief or fear or rage or whatever it was. It goes from one roar or one scream or one terrible sound of pain to starting to articulate it. It’s the articulating that becomes poetry. But it doesn’t become information at that point. It’s closer to translation. It’s translating something that’s there, that is only to a degree expressible.

Joel Whitney: So translating really helps because it helps illuminate that relationship?

W.S. Merwin: Yeah. Translating is about articulation. It’s not just about carrying something over. I mean, after all, if you translate poetry, which as we know can’t be done… but, you know as much as you can, about what a passage or a line or any part of the poem means, what its prose meaning, what its denotation is, all of that, and don’t dismiss it—this is the way I feel about it. And that’s not what makes it work in English either. And you go on and realize that, yeah, there’s another way of saying that, and then you think, well, there’s still another way of saying that, until you get a way of saying which seems closer to being a poem and closer to… just as close and probably closer to the full meaning of the original. I think of translation that way. After all, translation is a confusing word, because it’s come to mean everything from prose trot to something that takes vast liberties with the original. The translations, so-called, of the sixties were pretty free and easy. You wouldn’t recognize the original. Clarence Brown said to me about someone who did a translation of [Osip] Mandelstam: “Well, nobody would recognize that as Mandelstam except by dental impression.”

Joel Whitney: You mention rage, grief, erotic passion as inexpressible emotions behind the poetic impulse. Or behind the primal urge to express. It seems of those three, grief—perhaps over loss or absence—is the one you have been most concerned with.

W.S. Merwin: I think it’s quite possible that language begins with grief. You know, you see the Iraqi woman whose husband has just been killed by a bomb in front of her and that open mouth. That’s the origin of language right there. Grief and joy are never far apart.

Joel Whitney: Octavio Paz wrote of the first people coming out of a cave and looking up at the stars and just being filled with awe and joy—and he said there’s where poetry came from.

W.S. Merwin: Yeah, because joy, too, is inexpressible. When you come to that moment, what can you say? You just look.

Joel Whitney: Let’s talk about some of the writers you did translate. Did you meet Borges?

W.S. Merwin: I did. I introduced him one night at the 92nd Street Y [in New York] many years ago. Very young. And there’s a picture. I think it was Jill Krementz took it, and she showed it to me many years later. And she said there’s a picture of me sitting on the arm of the easy chair in the green room. And in the easy chair is Borges, looking up. And we’re having an obviously very close conversation. She said, Do you remember this? I said, I not only remember it, I remember the evening very well and I remember what we were talking about. She said, What was that? And I said, He had just recited by heart, in English, Milton’s sonnet, “On His Blindness,” and we were talking about that poem. And how he loved it. And, you know, Milton wrote that poem as quite a young man and there’s a lot of piety… the Puritanical piety that runs through Milton’s poems. But it doesn’t wreck the poem, because he’s talking about being guided by this passion, which in his case, he doesn’t separate his religious belief from his poetry. He never did. Although I think the more secular poems of Milton are some of his most beautiful. One of the greats is “On His Deceased Wife,” remember? Where he says, “Methought I saw my late espousèd Saint/ Brought to me like Alcestis from the grave.” And so different from the sonnets of Shakespeare.

Joel Whitney: So that was the thrust of your conversation with Borges. Did you stay in touch with him?

W.S. Merwin: Not really. I don’t think he wrote letters very much by then; he dictated letters. And when he gave talks, he did them more or less from memory. He ad-libbed them and he made them up to some degree. Was it Seven Nights, that book of talks that he composed and delivered after he lost his sight, when he couldn’t read off the platform anymore? But you know he lost a lot of his sight quite early.

Joel Whitney: It seemed to come in stages.

W.S. Merwin: It was genetic. I mean he had had parents and grandparents, all of whom had lost theirs.

Joel Whitney: His dad had lost much of his sight.

W.S. Merwin: Was it his dad? I thought it was his mother’s side too.

Joel Whitney: His dad took the family to Europe in part because he needed eye surgery. There’s a [relatively] new biography by Edwin Williamson.

W.S. Merwin: I haven’t read that one.

Joel Whitney: But you clearly love literary biography, and encounters. Wasn’t there another Borges encounter that had to do with Robert Graves?

W.S. Merwin: Yes, with Alastair Reid. Alastair succeeded me in the job with Robert Graves [as his assistant], and then he and Robert had a falling out. Robert did with everybody. Alastair tried to stay friends with Robert and he did stay friends with Beryl [Robert’s wife], and would go out and visit her. He had a house of his own on Mallorca and his son lived on Mallorca, too. So he was in Mallorca quite a lot in those days, the last years of Graves’s life. And in Palma there was one cafe that we all used to go to, Figaro. When we finished our shopping we would go and drink at Figaro. Alastair went and he was having a drink and he looked and a few tables away, there was Borges and [his wife] Maria Kodama. And he went over and spoke to Borges and said, “What are you doing here?” And Borges said, “Oh, I’m on a pilgrimage” [Merwin imitates the Argentine accent, laughing]. And Alastair said, “Yes, what kind?” And he said, “I’m going to see don Roberto Graves.” So Alastair thought, Oh my god. Because this was in the early eighties. Robert had, as Alastair said, lost his marbles. And he was really gone. And he was a really big man and he kept falling out of bed, and so they had to put him in an oversized crib, with a thing [bars] around it.

And Alastair thought, This is going to be a disaster, him going out to see Robert. And he said, “Would you like me to come with you?” And Borges said, “Oh yes, I’d love that.” So in those days you still took the little train from Palma out to Soller and then took a car up to Deià . They did, and they went to see Beryl and Beryl let them in and she was a little bit anxious too. You know, Robert didn’t like other writers… I’m sure he never read any Borges. And he didn’t know who it was anyway. I mean, he was just lying in bed, gaga. And Borges tried to make conversation and was talking to Robert and was getting nothing back but the occasional sort of monosyllabic nothing. And Alastair finally said to Borges, “I think that don Roberto is probably a little bit tired.” And he took Robert’s hand and brought it out through the bars of the crib. And he took Borges’s hand and put it in Robert’s hand, and there they were for some minutes, holding hands. In totally different worlds. Completely unaware. And that made a good moment for farewell and he could say Borges could make his rather courtly farewell to Robert, which was unacknowledged, and off they went. It’s totally grotesque to think about, one totally blind and unaware, and the other completely gaga and unaware.

Joel Whitney: That’s sort of remarkable. Tell me more about your translating work. The East Window: Poems from Asia offers that terrific series of “figures”—those haikulike, proverb-like epigrams from Korea and the Philippines and elsewhere. And you translated so much from South America, including Borges, and from Europe. To account for this much, you’ve made it clear you worked with co-translators to cover languages you don’t speak.

W.S. Merwin: One of the (I think) good but dangerous ideas that came out and was acted upon in the sixties was that it was not necessary to know the language. You could work with someone else. The other idea that was even more dangerous was that you could write your own poem on the material that was there in the original poem. Which is something that should have been explored but not clung to as a right to do that. Because it’s a little misleading and shouldn’t be called translation. It should be called a version or adaption or something quite different that makes it clear that you don’t trust this as a translation. Because translation is a precious thing on its own and not everything is a translation. I mean, the pony is not a translation either. I think one of the ideas is that you could work with somebody else. When I was asked to do a Mandelstam obviously they must have known I didn’t know any Russian. And I said I would only conceive of working on Mandelstam with Clarence Brown.

Clarence was the guy who got Mandelstam’s texts out of Russia. They had never been published. He died in a prison camp. They got rid of him. And his wife memorized all of the Mandelstam and for thirty years recited it to keep it going. And when she began getting older, she recited all those poems to Clarence, who wrote them down on her kitchen table and smuggled it out of Russia. That became the New York edition of Mandelstam. I said I would only do it if I could do it with Clarence. And he said he would only do it with me if I would promise not to try to learn Russian. He said it would just confuse things. But every translation is limited. Clarence said wonderful things in the course of that work. I was depressed about one of them one day, and Clarence said, “Don’t worry. No translation ever ruined the original.”

Joel Whitney: Now, what are you planting here and what are the long-term plans for the Merwin Conservancy?

W.S. Merwin: We seem to be involved in this vast effort to turn the whole world into Southern California. I fell in love with this valley, Peahi Kahawai (Peahi Stream). But it’s had no water in it for one hundred and fifty years. The planters cut it off and then they built the highway out. The source of water was on the other side of the road. So there’s no water. And of course, that drove the Hawaiians off because one of the things the planters wanted was to get rid of the Hawaiians along this coast. And they did pretty effectively. But here it happened sooner than in other places, because of having cut the water. But you know the ‘oma’o has been singing to us all the way through and there have been birds here all the time. This land was wasteland. But the upper land here is what has been devastated. But down in the stream bed, they let it alone. It hasn’t been bothered since the Hawaiians were here. That’s another reason to save it. And there’s at least one Hawaiian grave and a couple of pits for roasting pigs and things down in the valley. And I love it, and thought I would start by trying to restore Hawaiian rainforest, which you can’t do. Then I got fascinated by the native palms. There are three of them you can see from here—the ones with the big fans. They’re all natives of Hawaii. They’re Pritchardias. And I got more and more interested in every aspect of palms and started corresponding with botanical gardens, and you can get seed (you can’t get seedlings).

Joel Whitney: The disappearance of the topsoil is why you can’t restore rainforest.

W.S. Merwin: They’ve lost all the topsoil. By planting the way it’s been planted since the seventies, it’s changed. And a lot of the humus has come back. The mini-climate has changed. The water has held, doesn’t run off. A lot of change. I wanted to put the canopy back. Because, if you deforest, you lose a lot of the water, just with the tropical sun. Constant sun on the soil just destroys all the humus.

Joel Whitney: How much of the work out here do you do yourself?

W.S. Merwin: I do far less than I used to. I used to work three or four hours a day and then all of the weekend. I don’t do it now, partly for health reasons, because I had an operation that reduced my stamina. But also because of all the other things that keep me from getting out into the garden as much as I want to.

Joel Whitney: The laureateship adds to the pile. The Library of Congress will pushing for appearances, no?

W.S. Merwin: No, no. That was the deal. I said—when Professor Billington [of the Library of Congress] asked me to do it—I don’t want to come and spend a lot of time in Washington and wear a suit all the time and do all that. It’s just not the way I want to live. I said, “Nobody takes it seriously that I don’t want to leave the garden, but that’s the fact.” And I love our life here. And he said, “Well, you can pretty well do it on your own terms.” And it’s gonna circle around the two trips we take to the mainland every year anyway, one in the spring and one in the fall.

Joel Whitney: I like the idea of you as poet laureate, especially given that you’ve written some of the best antiwar poetry in English. But I understand you were once in the military. Did you tell Terry Gross you were locked up in a military brig?

W.S. Merwin: This was when I was eighteen and in the Navy, and realized I really made a terrible mistake enlisting, and I went out and asked to be put in the brig because, I said, “I made a terrible mistake and I expect to have to pay for it. But I will not obey anymore orders.” I still feel the same way.